What art have I seen? Reflecting on encountering Sturtevant’s work at CAAC

How could I not know about this artist’s work? Repetitions of Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Joseph Beuys, Claws Oldenberg, and other younger artists including Félix González-Torres and Paul McCarthy.

Félix González-Torres Untitled (America, America) in the Whitney collection and Sturtevant’s repetition below at CAAC.

Félix González-Torres’ Untitled (Blue Placebo and Untitled installed for an exhibition and Sturtevant’s repetition Untitled (Blue Placebo) installed at CAAC below and together below.

From the exhibition brochure:

“Difference does not arise from the contrast between the identical [the thing?] and the opposite, but from the depth that emerges in the act of repetition. In that space where repetition reveals the hidden, where insistence displaces the obvious, lies the core of Elaine Sturtevant’s work. Her radical practice does not seek to imitate or reproduce but to question. By repeating iconic works of her contemporaries, Sturtevant conducts a conceptual analysis that transforms notions of originality and authorship, demonstrating that creation does not reside in pure invention but in the ability to dismantle the systems that assign meaning and value to art.

At the core of Sturtevant’s practice lies a profound engagement with power: how it operates, how it is observed, and how it is internalized. Her work resonates with Michel Foucault’s theories on systems of control, particularly his concept[ion] of the [way that the] panopticon [works]. Much like Foucault’s model, Sturtevant’s work places both the creator and the viewer within a dynamic of observation and complicity.

…

Gilles Deleuze, in his work Difference and Repetition (1968), argues that the ‘new’ does not arise from the repetition of the same but from the affirmation of difference inherent in the act of repeating. Sturtevant’s repetitions, following this line of thought, diverge entirely from imitation or appropriation to become deliberate conceptual interventions that expose the mechanics through which meaning is constructed in art and culture.”

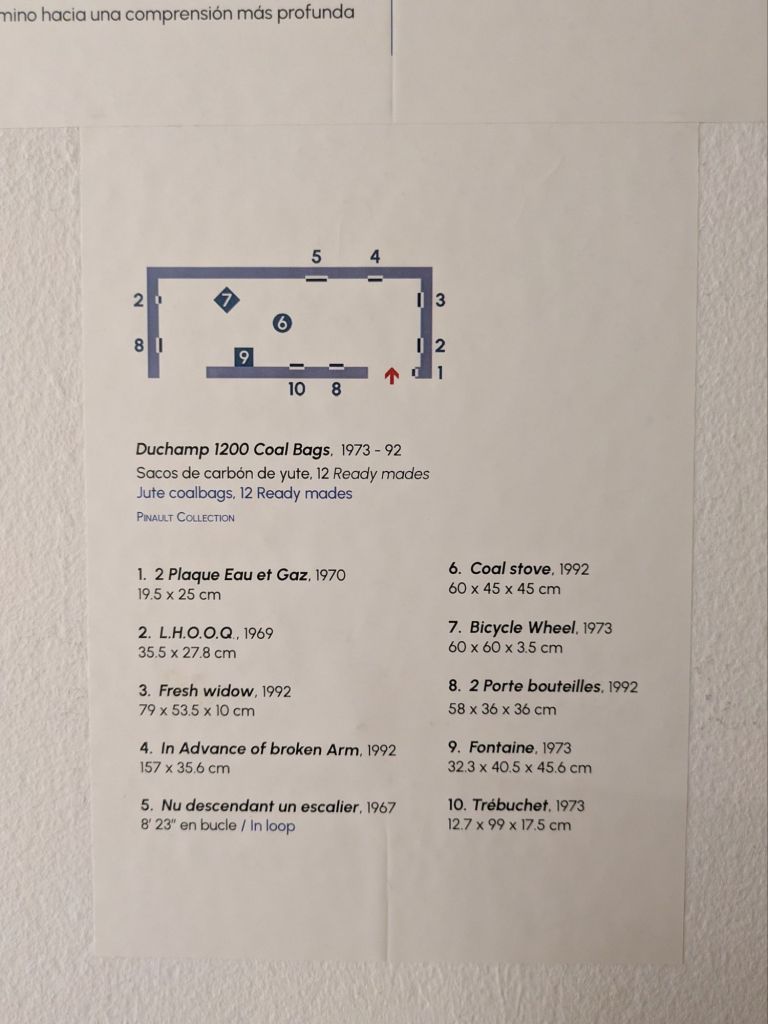

The ‘Duchamp room’ had a collection of works including Duchamp 1200 Coal Bags in the ceiling and a number of other works arranged in a conventional if slightly dense installation – the fountain, the bottle rack, the bicycle wheel.

Duchamp’s installation of 1200 Coal Bags for the International Surrealism exhibition in New York in 1937 the floor was covered in leaves and it was darker and less of a greatest hits installation – it looks denser in the photograph.

There is a film in the space too, entitled Nu Descendant Un Escalier, which seems to make use of Duchamp’s only piece of film, but remakes it with footage of mostly naked women descending stairs, and includes a title screen (below). Where all the other works are copies, this uses some different elements. It’s not the only invention hidden within the copies (see Beuys and Johns below). It’s also interesting that there are 2 bottle racks and between this and another room 7 Fresh Widows.

The exhibition literature argues, discussing Sturtevant and Warhol and in particular the work with Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe silkscreen, “This implicit collaboration between the two artists encapsulates the tension between originality, authorship, and repetition, positioning Sturtevant as a key figure in the development of conceptual art.”

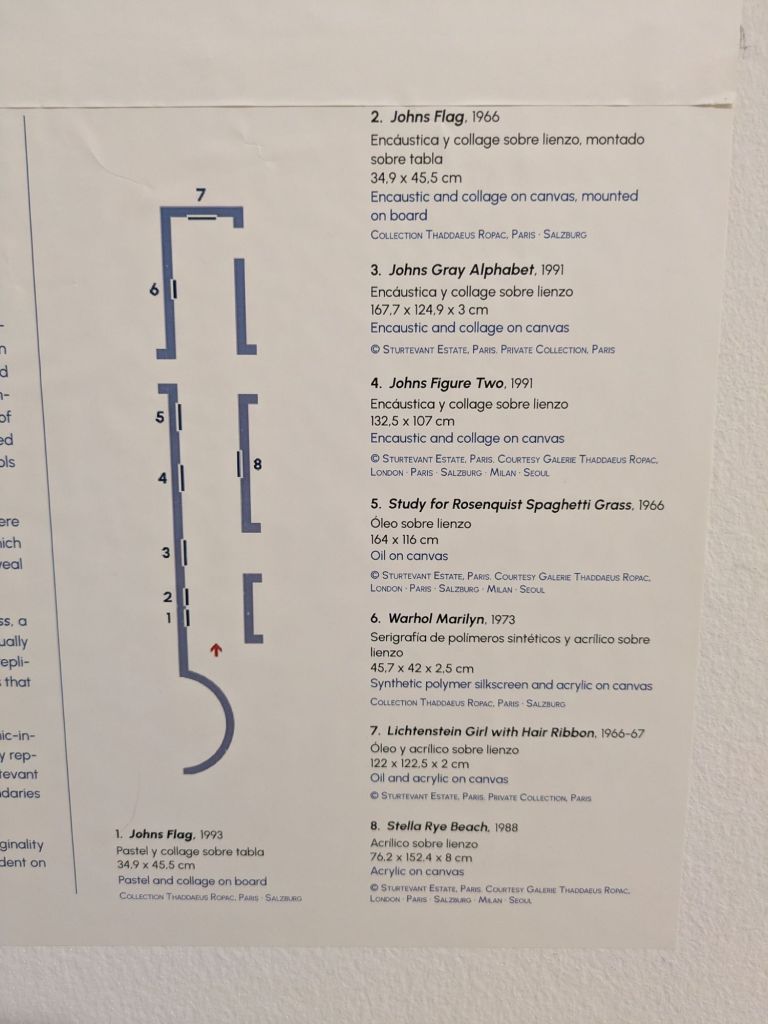

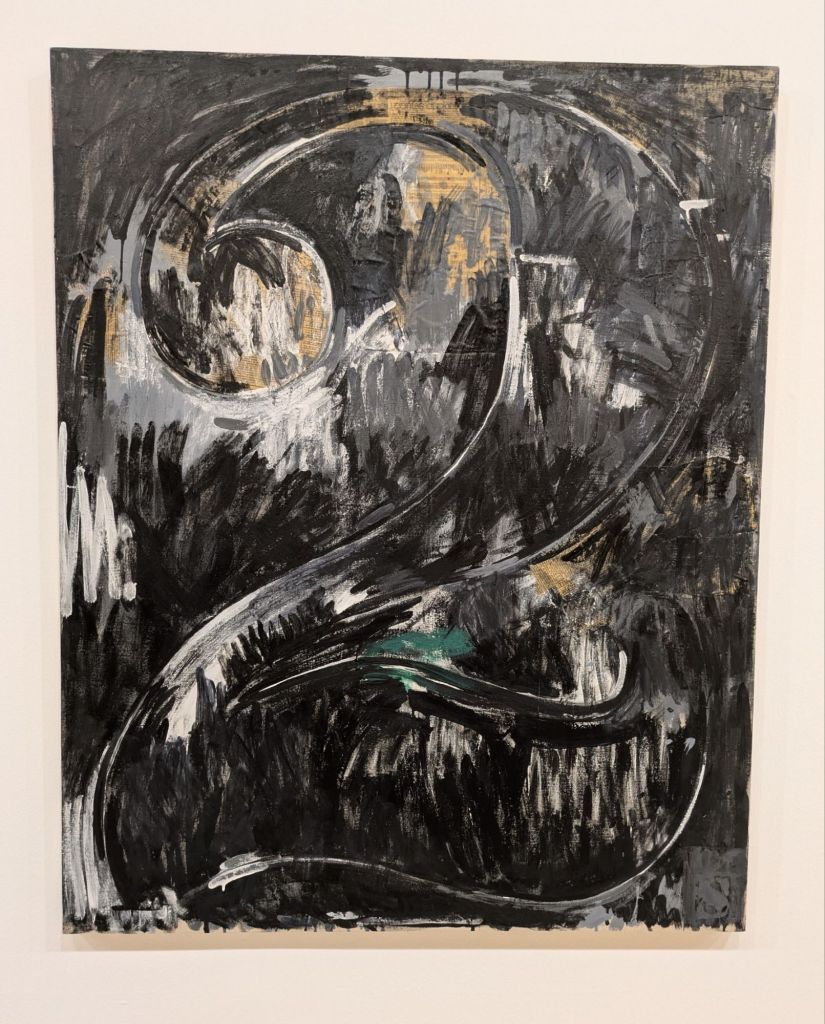

Of course this is conceptual but it is also made – the instruction is the existing work. There are Jasper Johns’ American Flags and numbers. The Figure 2 below is painted on newsprint and I can’t find one quite like it using Google.

Suze Kay discusses these works at length focusing on what sort of reproduction Sturtevant was making, pointing out that even though Sturtevant is using Warhol’s silkscreens, they are poorly made. Kay says “Especially in comparison to the original, but even alone, the unique nature of Warhol Marilyn is clear. The less-experienced Sturtevant produced a hazy image with poorly matched color fields. The boundary between the image’s cheek and hairline fuzzes into a dark smudge. Thin commas of turquoise sit haphazardly above the Warhol Marilyn’s eyes, just barely mimicking eyeshadow. The image’s surface is further flattened by the angry, sloppy smudge of red that slashes across its lips.”

Kay had earlier described an encounter with one of Sturtevant’s Frank Stella’s saying “Ingrid Langston … tells an amusing anecdote about a pair of viewers looking at one of her Stella repetitions. “Somebody walked in and said: That’s the worst Stella I’ve ever seen. And then somebody replied, Yeah, but the best Sturtevant.”

Sturtevant was subject to much hostility and largely ignored in the US. Kay describes her works as ‘cruel’ in what they do to the works of the male artists she is repeating.

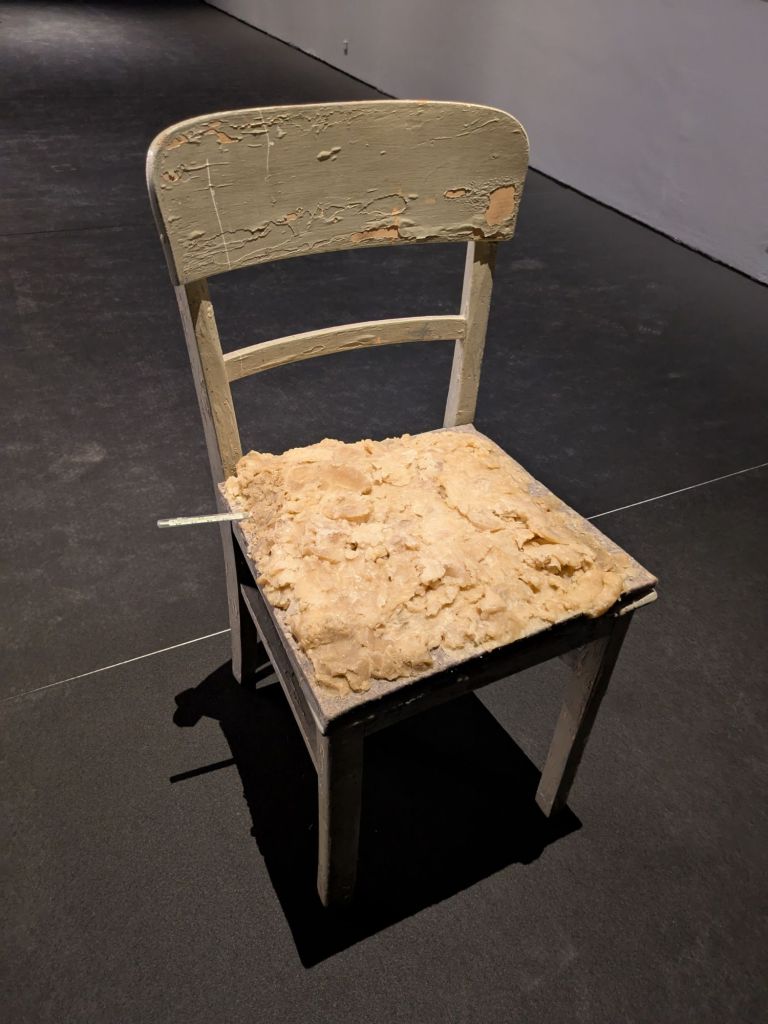

There is a room with two chairs and a set of windows – the windows are entitled Fresh Widow, a work made by Duchamp in 1920. There are 6 here and another in the Duchamp room. The chairs are attributed to Joseph Beuys.

One is entitled Beuys Fettstuhl and is, apart from not being ina climate controlled vitrine, very close to the one in the Tate, including the thermometer sticking out the side.

The other is entitled Beuys Vor Dem Pultstuhl and I’m not sure it is a copy though it uses wax and lead and brick and a leaf, all very evocative…

On one of the corridor walls we find a wanted poster (coincidentally with a dragonfly).

And in a room at the end of the exhibition a video entitled Sturtevant Re-Run.

The Sturtevant Estate is according to the captions represented by Galerie Thaddeus Ropac. They also represent Robert Longo and in an exhibition of his works where he was redrawing other artists’ works they quoted on the wall part of an essay by Dominique Font-Réaulx

“Longo’s ambition was to translate these paintings into his own language, to free the language imprisoned in a work by recreating it in his own style, to grasp, through a process of remaking and reinvention, the artist’s thought, which is discernible through intention and in gesture.”

Sturtevant isn’t translating into her own language (even when she is inventing new examples). Rather it seems to me she is questioning whether an artist’s language should be understood as singular, that the is any claim to uniqueness. She is certainly playing with Walter Benjamin’s argument about the aura of work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction – she is showing that the aura is a fiction. I might not be able to find the Jasper Johns’ Figure 2 (though I haven’t looked in a catalogue raisonne) but even if I did I would still be faced with a dilemma – can the copy also have aura?

We might need to turn to another Marxist critic Frederick Jameson and his argument that we have seen a shift in Capitalism from production to reproduction, “…how late capitalism transitions from an economy of production, where one makes objects, artworks, and commodities, where the output is a product, to an economy of reproduction, where signs, images, and ideas are the ever-circulating outputs.” as it is put in Ruby Thelot’s essay ‘Art Making Machines’. It’s interesting to consider Sturtevant in this light because there is specifically production here – it is the production of male artists’ works with in some cases a ‘disturbing degree of accuracy’ that opens up the questions about authenticity and power. Kay provides a valuable gloss on this point, “Sturtevant saw a piece of art as consisting of three main parts: the object, the process, and the concept. In an original work, the artist is responsible for the creation of all three parts. For example, when Johns made his original Flag (1954, figure 3), these parts were inseparable. But for Sturtevant, only concept mattered. “Although the object is crucial, it is not important,” she once said, a statement followed by “Process is crucial but not important.” Sturtevant, by mimicking the original artist’s process and pulling directly from their imagery, found herself responsible only for the content of an image. This unique approach of repetition allowed her work to directly challenge the artist’s original message, or as Langston says, is how she “called out other artists on their own claims.”.

Sturtevant isn’t the only artist who has resisted being associated with a specific movement, in this case feminist art, but for me she contributes a very important dimension – recent arguments made for the centrality of feminist approaches e.g. Heartney et al 2024 would be complemented by Sturtevant’s project. And the creation of a body of work that so effectively, even “brutally” in Sturtevant’s own terms, takes on the dominant male artists of the time and draws out the understructure the work is resting on must surely be understood as a project with a gender and political core?

leave a comment