New writing

Three pieces of work that have all taken ages to get out are now published! They all bear on the Culture-based Climate Action agenda, the critical project to articulate the role and capacities of cultural actions across arts and humanities in addressing the nexus of crises: climate, biodiversity, and pollution.

Firstly, the article on Uncertainty and Indeterminacy resulting from events held between two environmental research projects – newLEAF and Creative Landscape Futures https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01426397.2025.2537772

Abstract: Landscapes, intentionally or otherwise, are often planned and managed in ways that create determined outcomes involving production, conservation, and aesthetics. While the focus of much research is on how to plan landscapes more effectively, this article explores how uncertainty and indeterminacy are inevitably also part of the research process. We present the results of discussions among a multidisciplinary group of researchers across the arts, humanities, social and natural sciences. We articulate discipline-specific understandings of indeterminacy and uncertainty and synthesise points of similarity and difference between them. Common concerns are with the limits of knowledge; conceptions of futures; the role of chance and change; and the dichotomy of action or ‘doing nothing’ in landscapes. We highlight arts research that works distinctively to develop subjectivities and create different relations with control and management. We emphasise the challenge of research to manage risks versus the need for indeterminacy to enable adaptation and promote novelty.

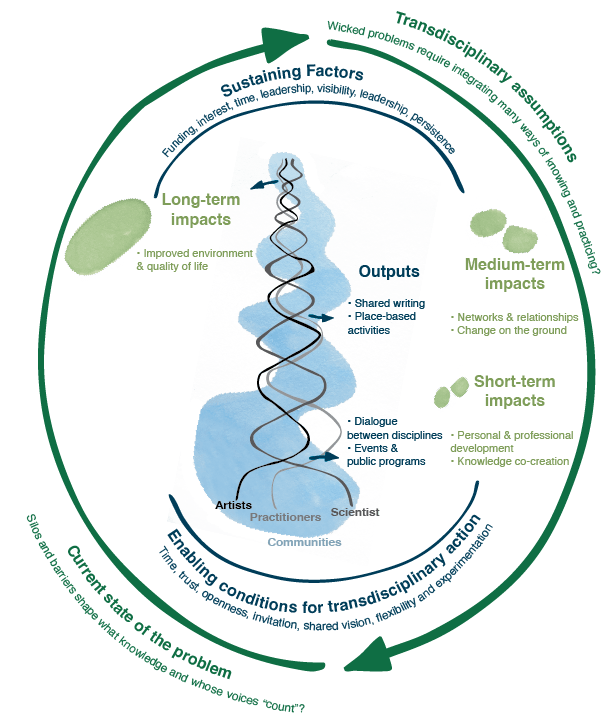

Secondly, a magazine article on developing a Theory of Change based on the NATURE PLACE programme of artists’ residencies with land and natural resource managers and researchers https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/2026/01/21/how-artists-help-to-transform-natural-resources-management-building-a-theory-of-change/

And thirdly, the article developing an analysis of the evaluations of artists, scientists, land managers and organisers of the NaturePLACE (formerly UFS Arts) program. This will be published in The International Journal of Social, Political and Community Agendas in the Arts.

Abstract: This paper uses a knowledge exchange-based approach to evaluation to explore the reported experiences of artists, scientists, and land managers participating in the ‘NaturePLACE Program’ (formerly UFS Arts), focusing on the period 2016-2024. The primary aim of the Program is to build understanding of and engagement with urban social-ecological systems through the arts. The approach to this evaluation draws on a range of literature on research in the arts, as well as research and knowledge exchange impact evaluation from the environmental research domain. The evaluation reported in this paper is distinctive in focusing on the interactions of participants rather than on perceptions of beneficiaries. The data analyzed comprises evaluations (n=49) submitted at the conclusion of the residency by six cohorts involved in the NaturePLACE program (2016, 2017, 2018, 2020- 21, 2022-23, 2024-25). This paper provides important insights into the impacts on artists, scientists, and land managers from transdisciplinary place-based work. Causes of impact not previously noted within the framework are identified as related specifically to the arts, including modes of sensuous aesthetic attunement, forms of focusing attention and eliciting public discourse, and shaping cultural imaginaries. Critical reflection also becomes evident as an aspect of capacity building.

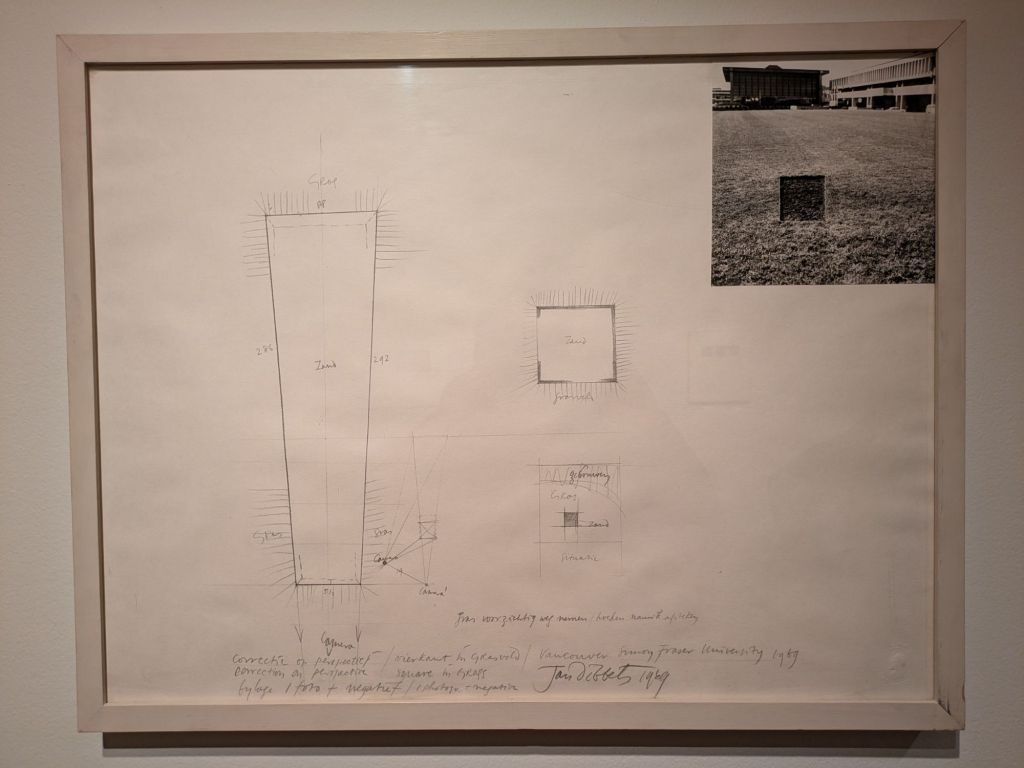

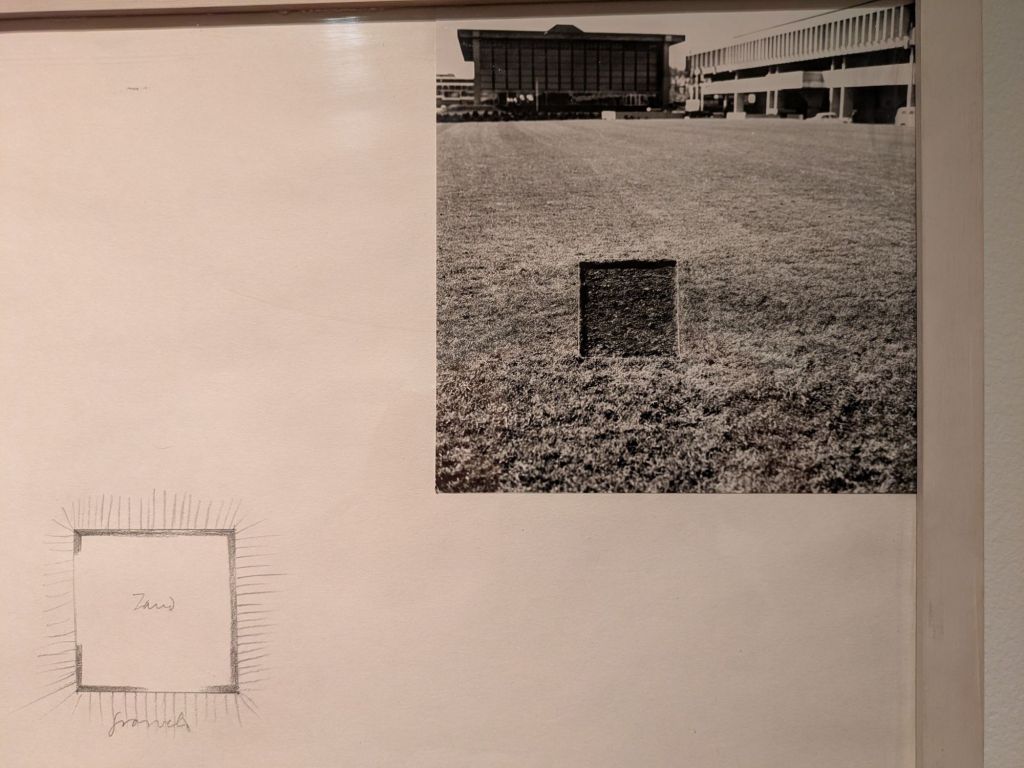

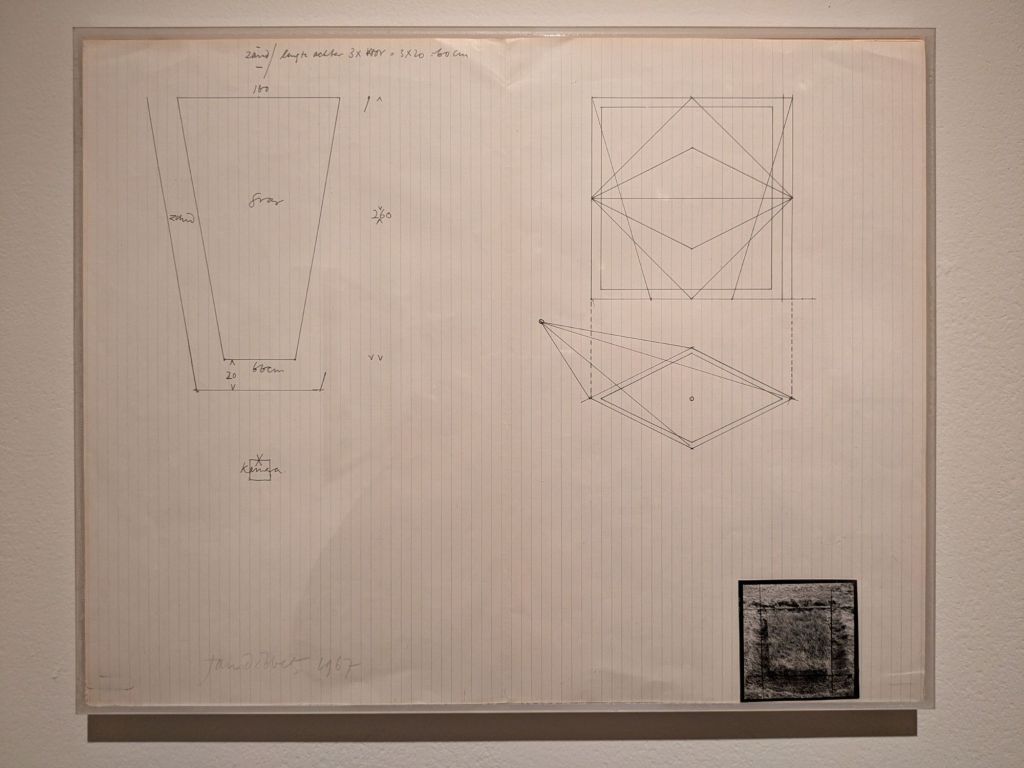

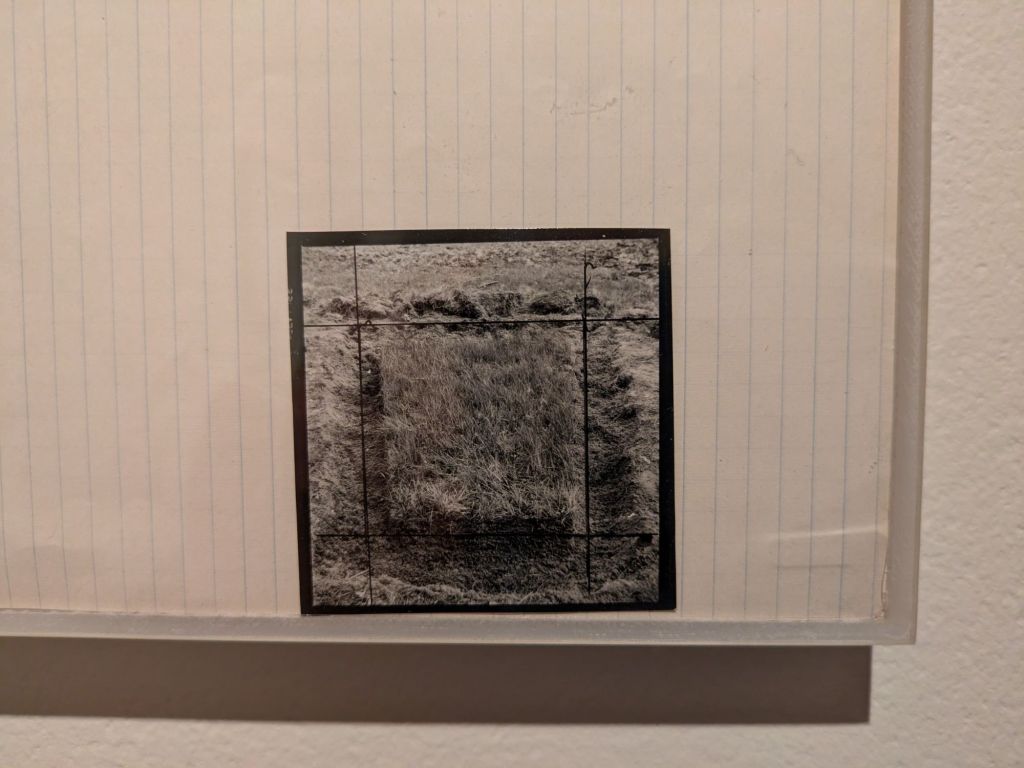

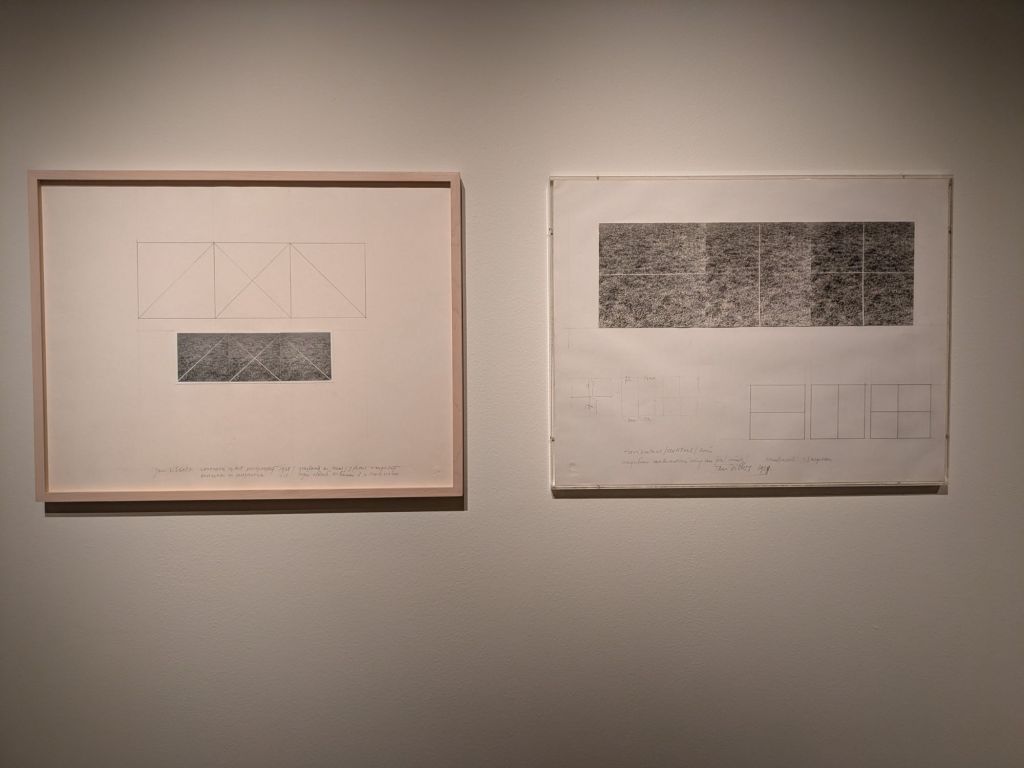

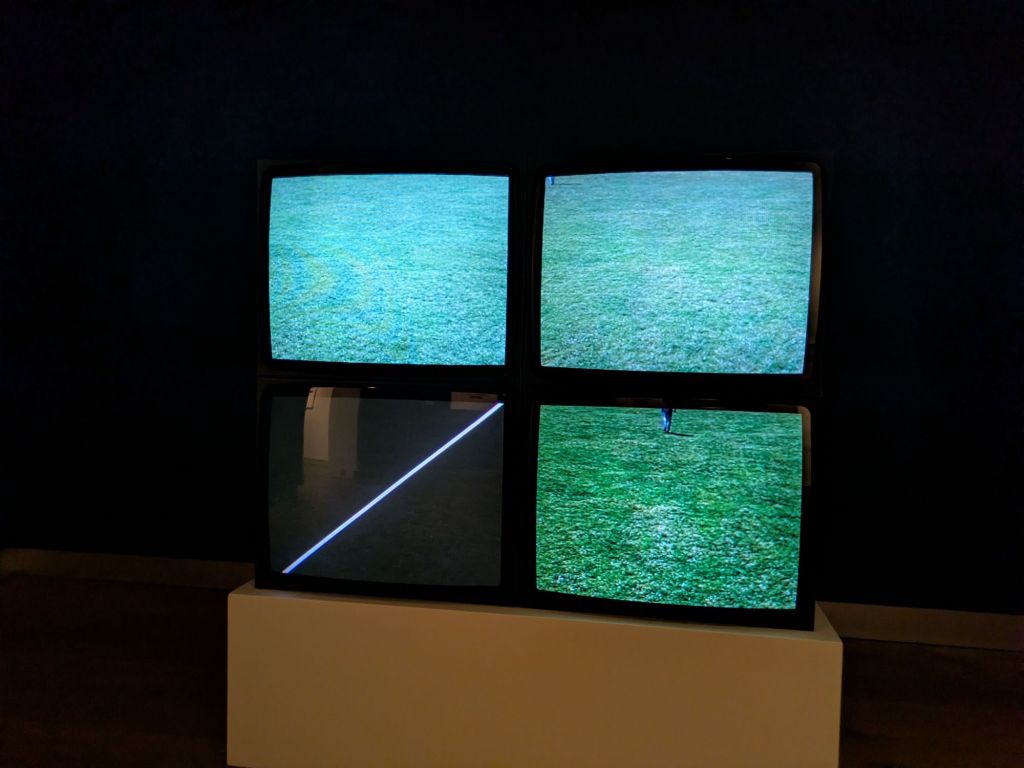

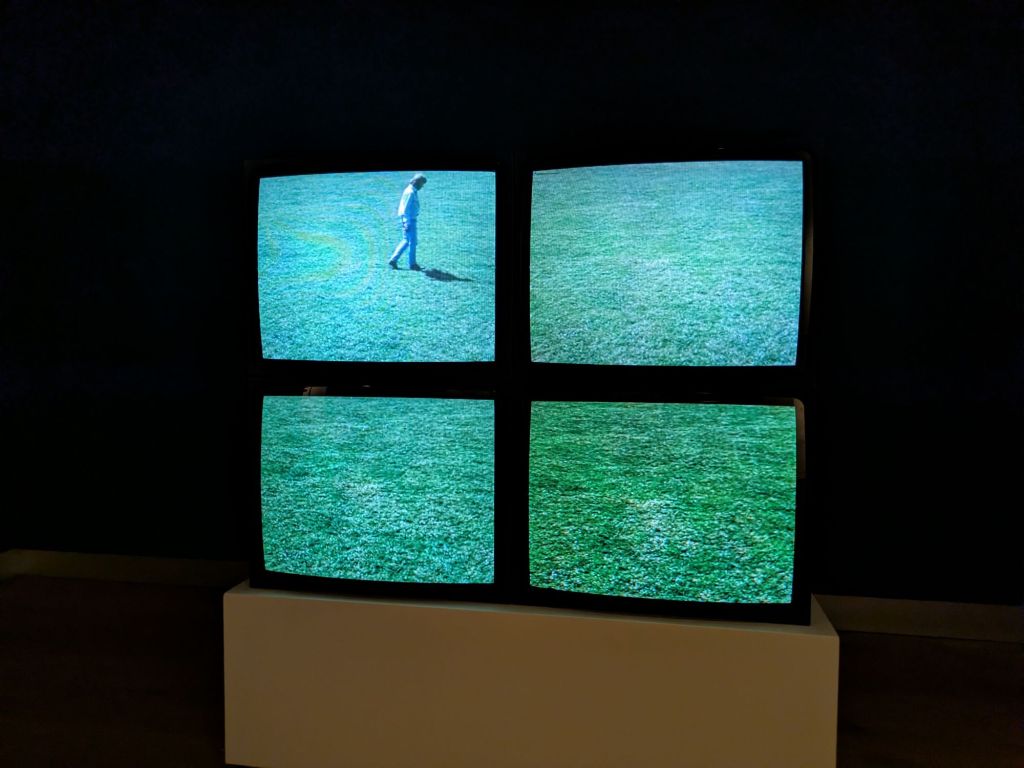

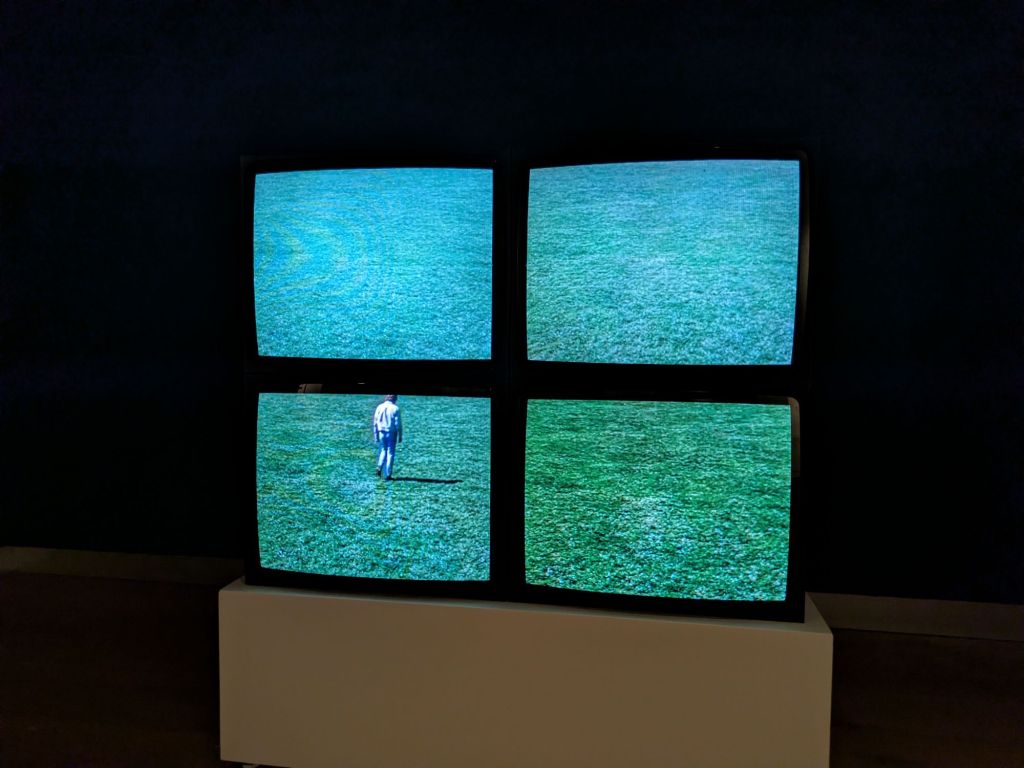

What art have I seen? Jan Dibbets

Grass

Years ago I made a list for an exhibition.

David Nash ‘Sod Swap’,

Durer ‘Great Sod’ (artist does ecology long before scientist),

Hans Haacke,

Lee Lozano ‘Grass Piece’ ‘No Grass Piece’.

This was all stimulated by Anne Douglas asking a bunch of us to respond to Allan Kaprow’s ‘Calendar’.

What art have I seen? Imagined Landscapes

Aberdeen Art Gallery

David Blyth

Alison Watt

Ian Hamilton Findlay

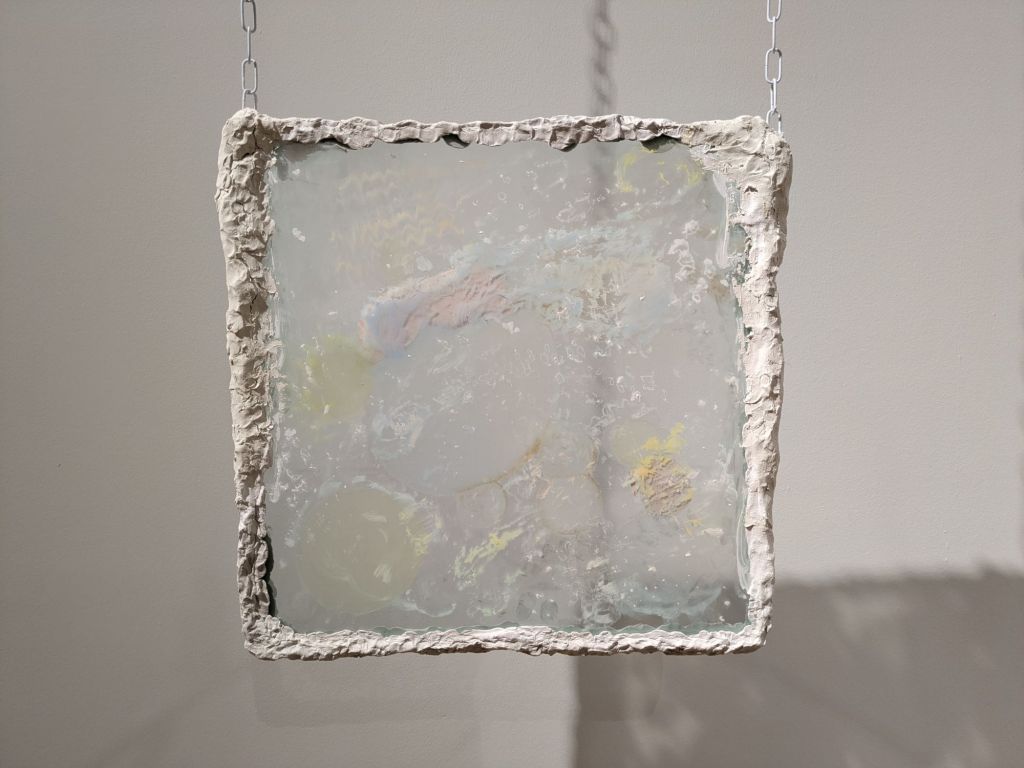

Karla Black

Glen Onwin

Fred Bushes

Andy Holdsworth

David Nash

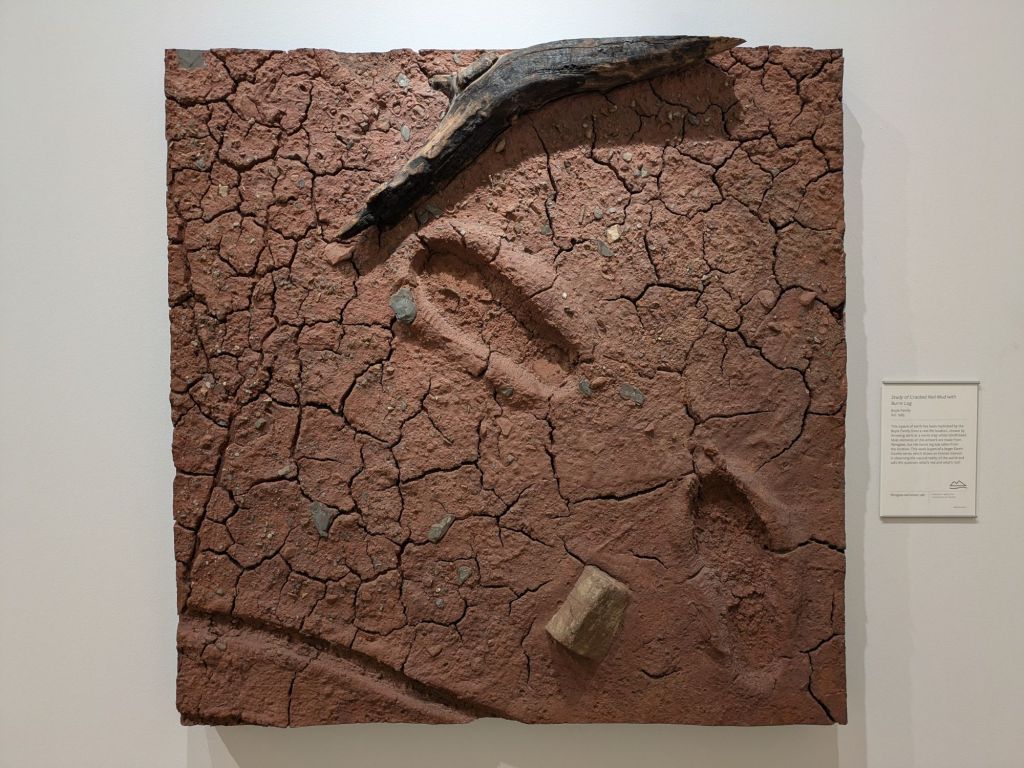

The Boyle Family

and others

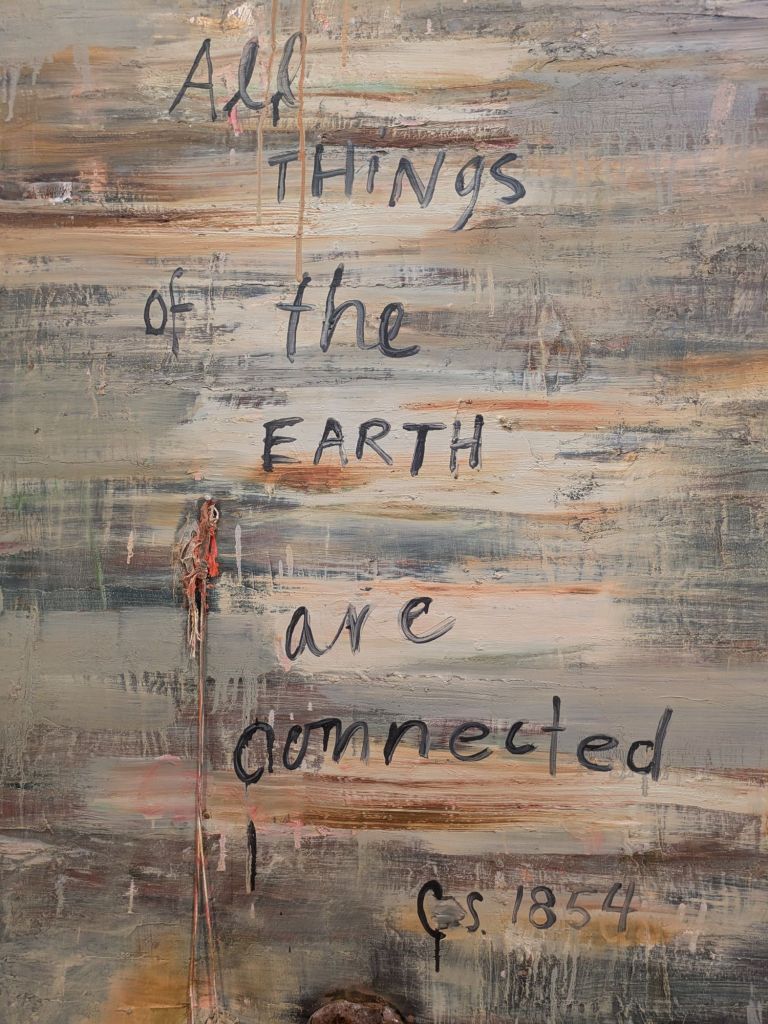

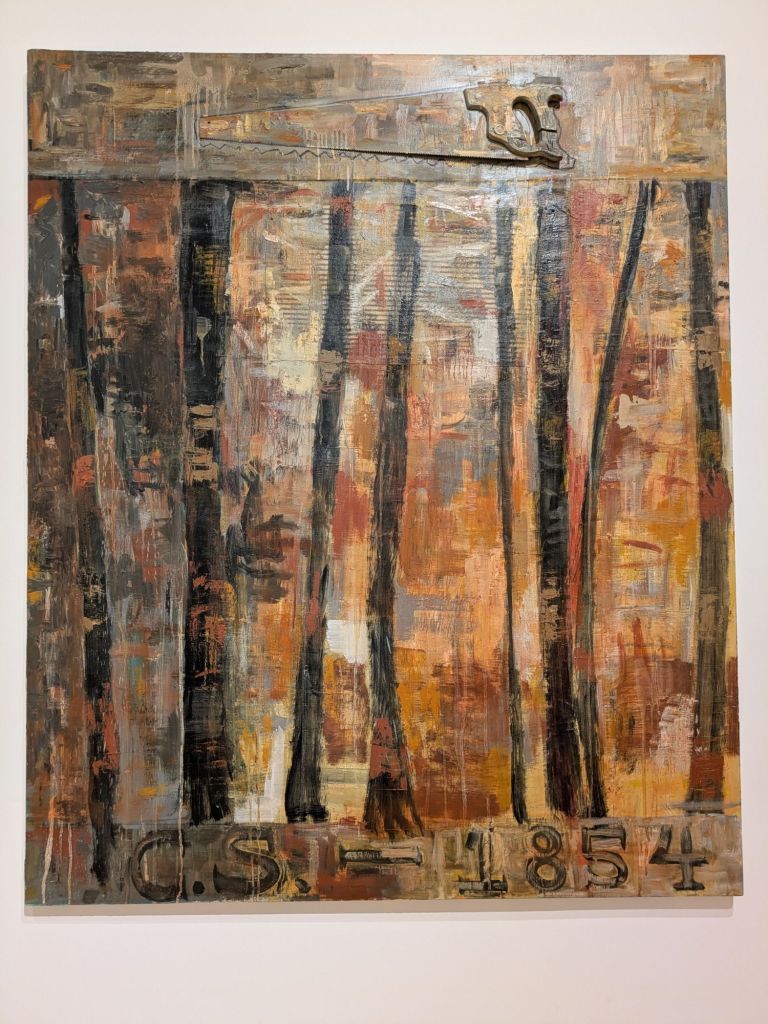

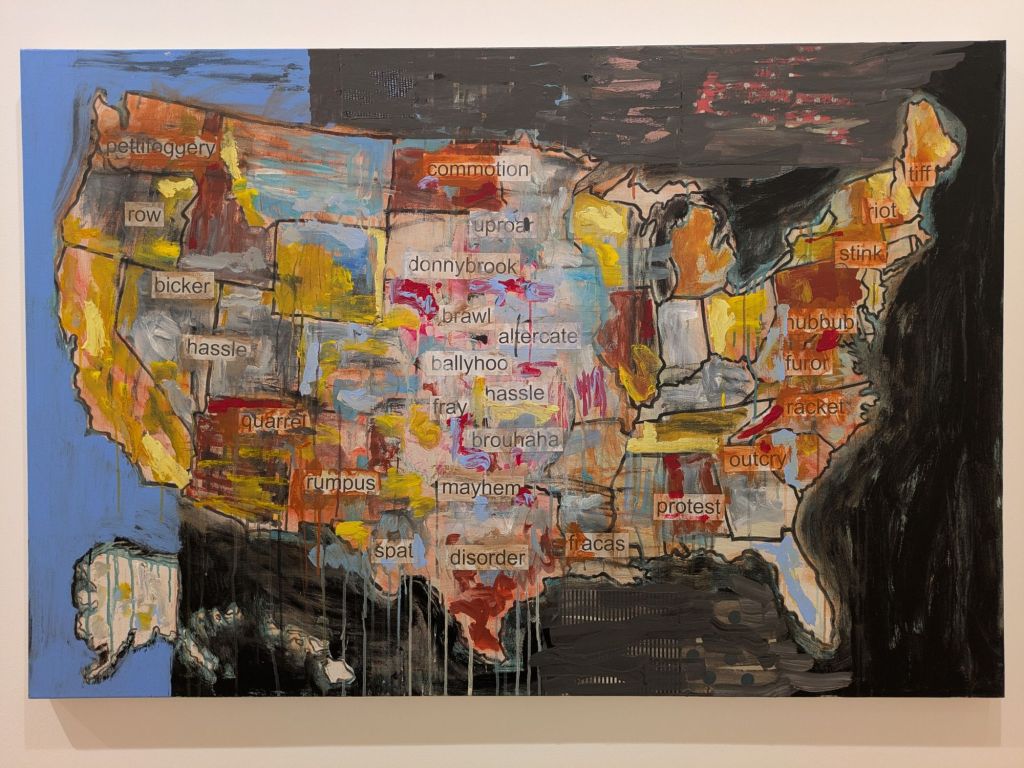

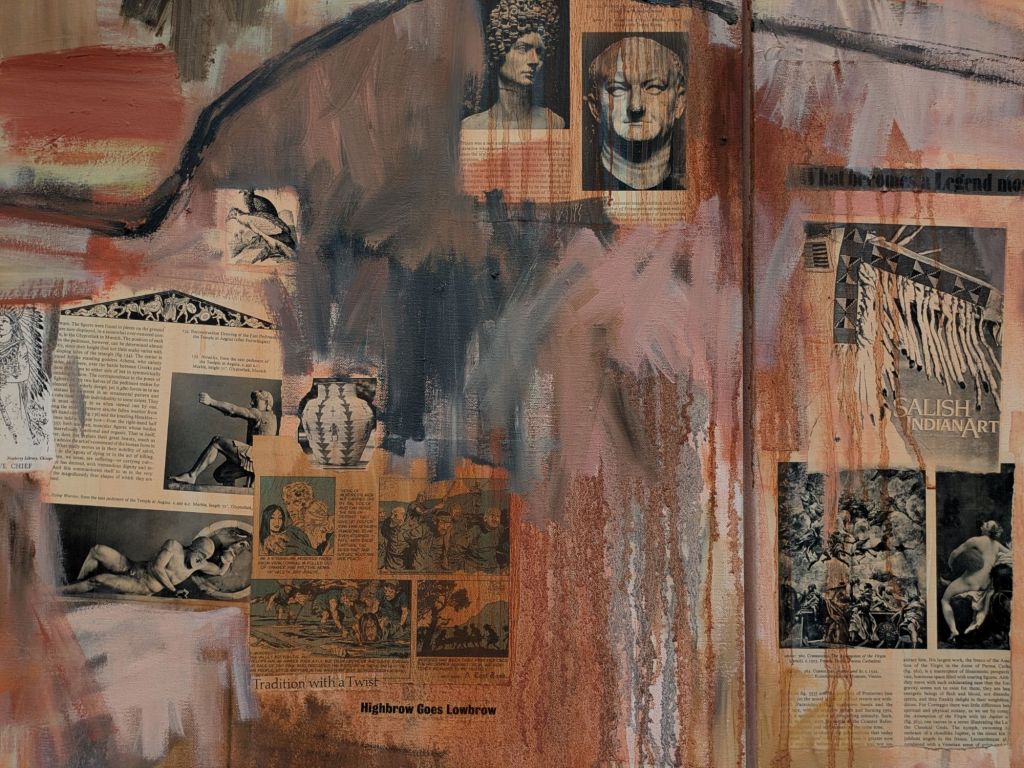

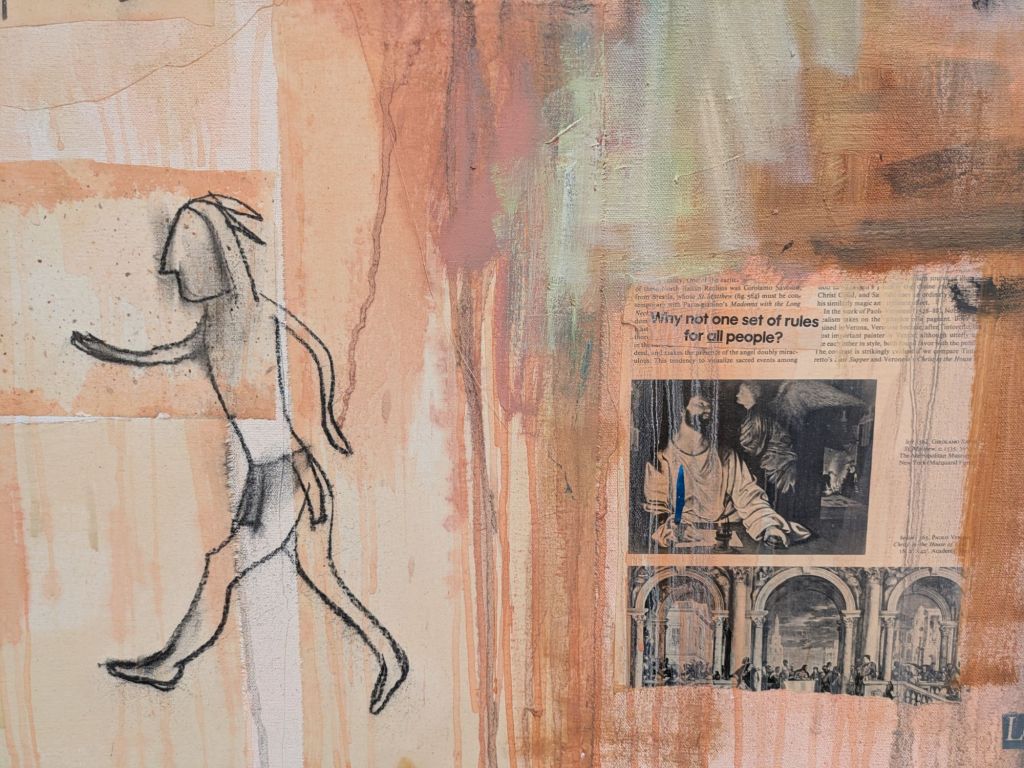

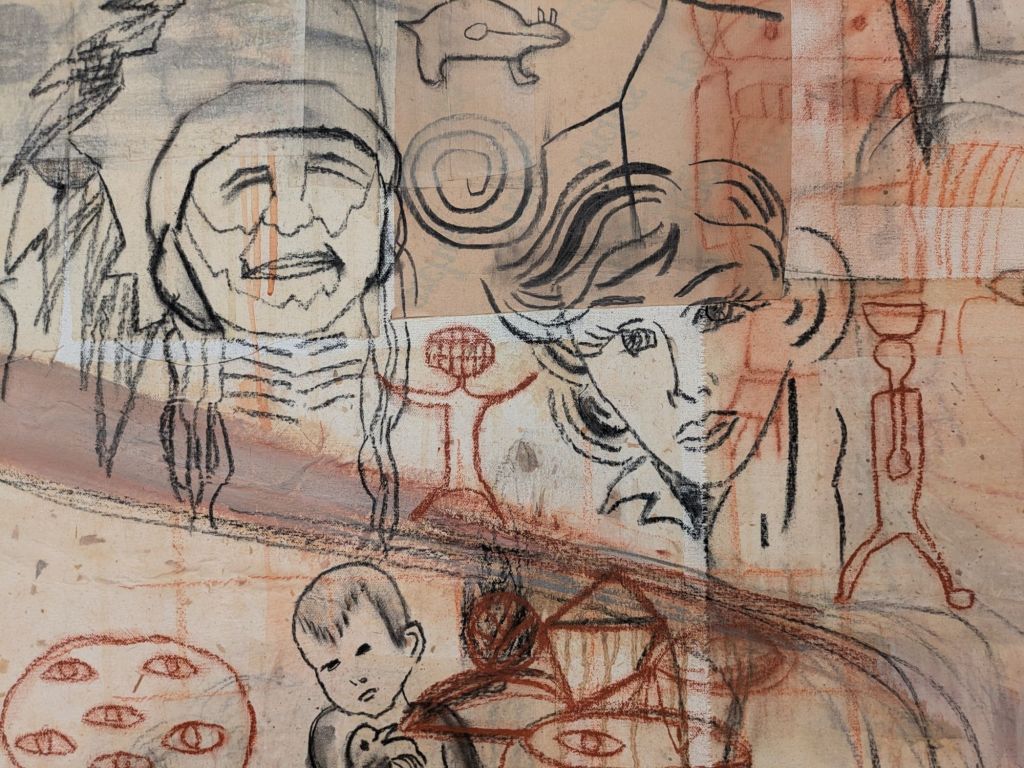

What art have I seen? Jaune Quick-to-See Smith ‘Wilding’

Returned for another visit having first seen the exhibition with Lara M Evans who generously shared her knowledge having worked with the artist extensively. In particular Lara drew attention to the references to Chief Seattle’s speech of 1856 – C.S. 1856 appears on some paintings.

Maps feature as a basis for other commentaries.

Lara suggested that Jaune Quick-to-See Smith used aspects of the abstract expressionist aesthetics in part because it was recognisable to white Euro American eyes. Within this cultures clash, stereotypes play out.

Upstairs is a wall made up of sketches assembled into another work when the artist was very ill. Above the stairs the boat of animals uses store bought plastic animals alongside hand carved.

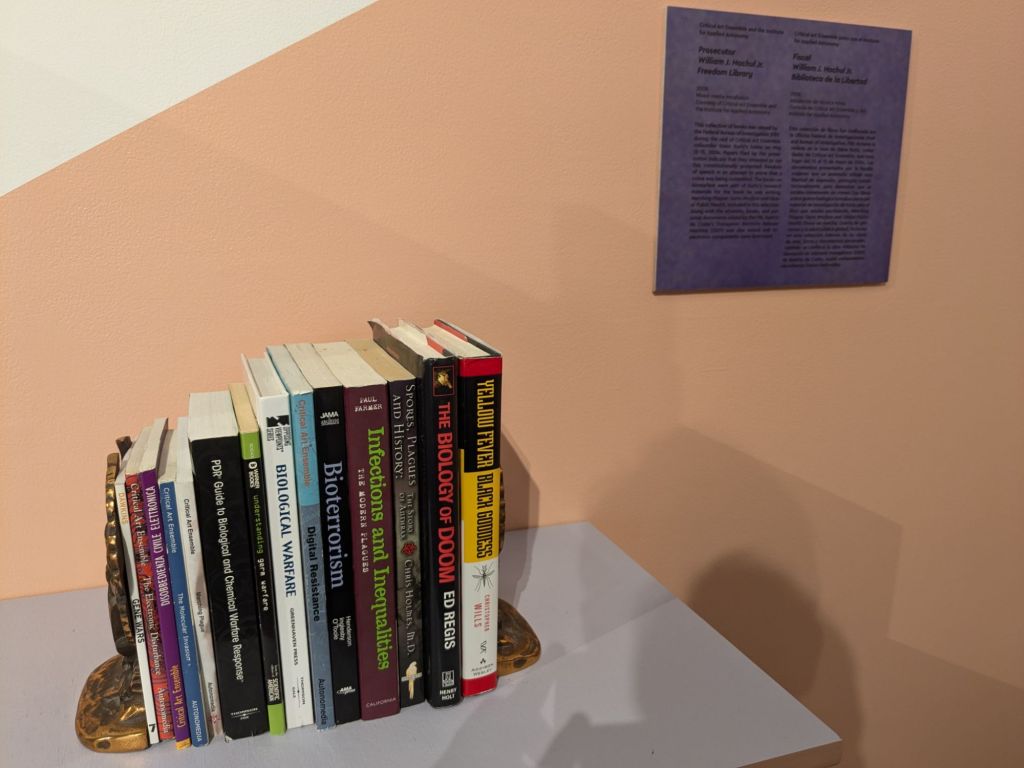

Gray’s Research Exhibition: ecoartscotland library as bing

ecoartscotland library as bing, 2016 ongoing, digital images printed on aluminium.

Riffing off John Latham’s 1976 statements about the ‘mental furniture industry’ and the waste produced by academia exceeding the waste produced by industry, these images reimagine the ecoartscotland library in relation to a bing in central Scotland, typical but also exemplary in its simplicity. Life has developed on the bing. The ecoartscotland library, whilst not waste (yet?), isn’t at present a substrate for vegetable or fungal life, nevertheless doesn’t have intrinsic value(?).

The ecoartscotland library has been exhibited as a working library and as a bing, and has formed part of other projects.

A reasonably up to date list of the contents of the ecoartscotland library can be found here.

The ecoartscotland library is somewhat related to The Martha Rosler Library.

Failure: Jane Trowell’s essay on Failure and Hope

Trowell, J. 2017. ‘Embracing Failure, Educating Hope: Some Arts Activist Educator’s Concerns In Their Work For Social Justice’ in (eds.) Serafini, P., Holtaway, J., and Cossu, A., artWORK: Art, Labour, Activism, London: Bloomsbury

What art have I seen? Reflecting on encountering Sturtevant’s work at CAAC

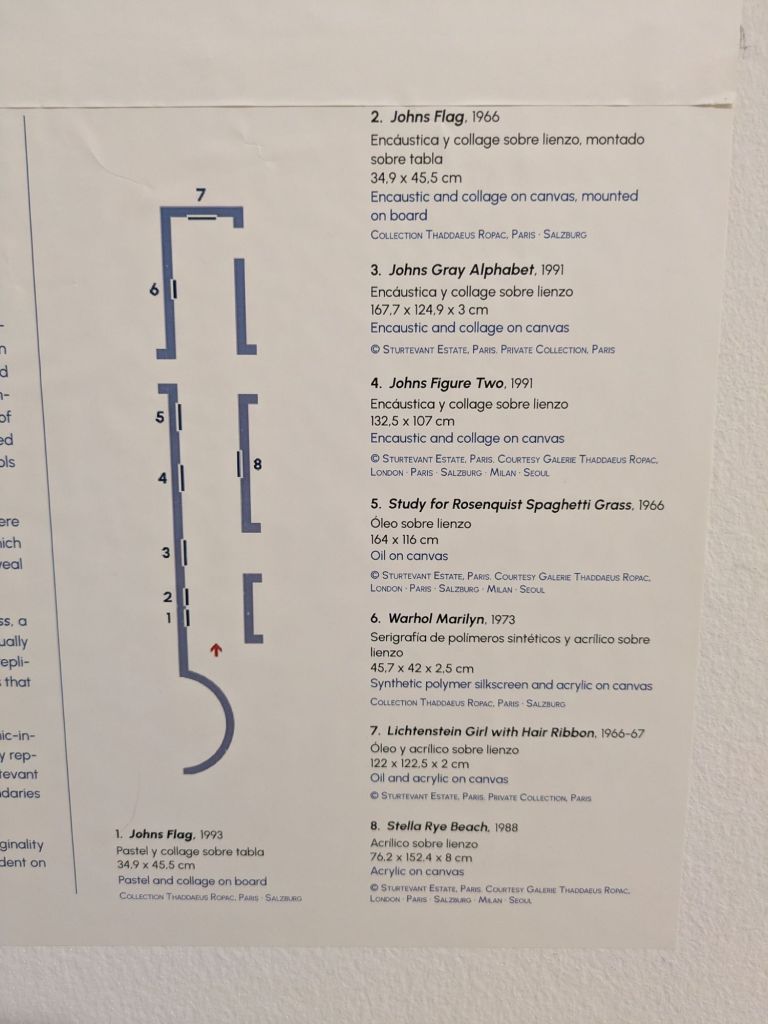

How could I not know about this artist’s work? Repetitions of Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Joseph Beuys, Claws Oldenberg, and other younger artists including Félix González-Torres and Paul McCarthy.

Félix González-Torres Untitled (America, America) in the Whitney collection and Sturtevant’s repetition below at CAAC.

Félix González-Torres’ Untitled (Blue Placebo and Untitled installed for an exhibition and Sturtevant’s repetition Untitled (Blue Placebo) installed at CAAC below and together below.

From the exhibition brochure:

“Difference does not arise from the contrast between the identical [the thing?] and the opposite, but from the depth that emerges in the act of repetition. In that space where repetition reveals the hidden, where insistence displaces the obvious, lies the core of Elaine Sturtevant’s work. Her radical practice does not seek to imitate or reproduce but to question. By repeating iconic works of her contemporaries, Sturtevant conducts a conceptual analysis that transforms notions of originality and authorship, demonstrating that creation does not reside in pure invention but in the ability to dismantle the systems that assign meaning and value to art.

At the core of Sturtevant’s practice lies a profound engagement with power: how it operates, how it is observed, and how it is internalized. Her work resonates with Michel Foucault’s theories on systems of control, particularly his concept[ion] of the [way that the] panopticon [works]. Much like Foucault’s model, Sturtevant’s work places both the creator and the viewer within a dynamic of observation and complicity.

…

Gilles Deleuze, in his work Difference and Repetition (1968), argues that the ‘new’ does not arise from the repetition of the same but from the affirmation of difference inherent in the act of repeating. Sturtevant’s repetitions, following this line of thought, diverge entirely from imitation or appropriation to become deliberate conceptual interventions that expose the mechanics through which meaning is constructed in art and culture.”

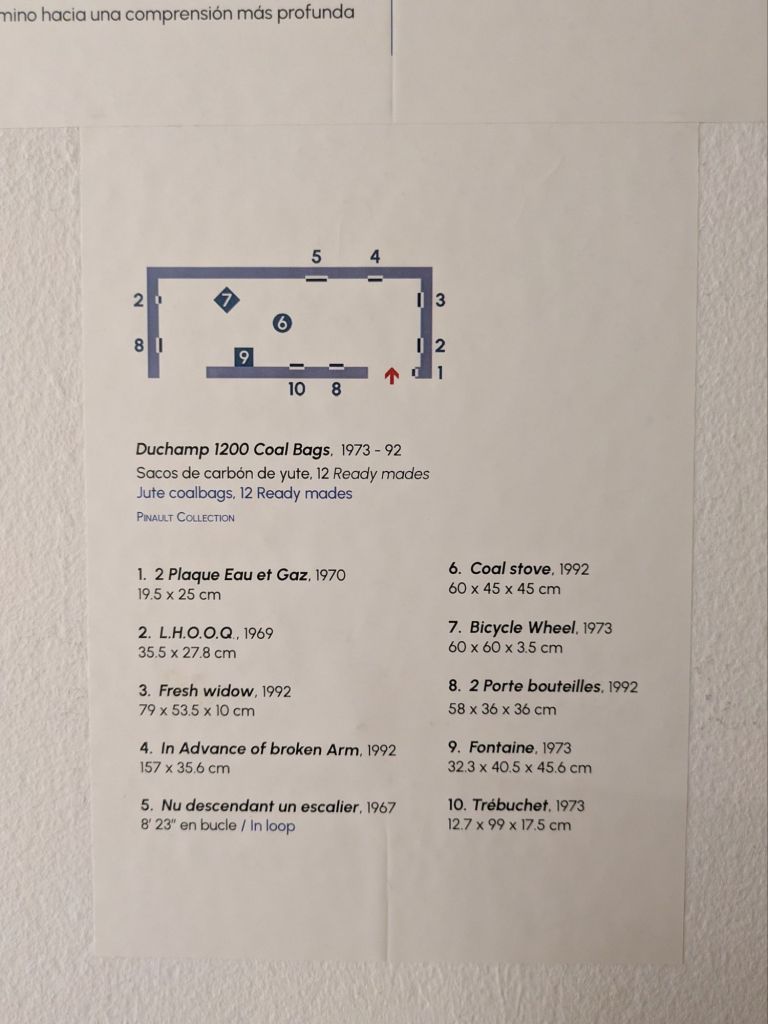

The ‘Duchamp room’ had a collection of works including Duchamp 1200 Coal Bags in the ceiling and a number of other works arranged in a conventional if slightly dense installation – the fountain, the bottle rack, the bicycle wheel.

Duchamp’s installation of 1200 Coal Bags for the International Surrealism exhibition in New York in 1937 the floor was covered in leaves and it was darker and less of a greatest hits installation – it looks denser in the photograph.

There is a film in the space too, entitled Nu Descendant Un Escalier, which seems to make use of Duchamp’s only piece of film, but remakes it with footage of mostly naked women descending stairs, and includes a title screen (below). Where all the other works are copies, this uses some different elements. It’s not the only invention hidden within the copies (see Beuys and Johns below). It’s also interesting that there are 2 bottle racks and between this and another room 7 Fresh Widows.

The exhibition literature argues, discussing Sturtevant and Warhol and in particular the work with Warhol’s Marilyn Monroe silkscreen, “This implicit collaboration between the two artists encapsulates the tension between originality, authorship, and repetition, positioning Sturtevant as a key figure in the development of conceptual art.”

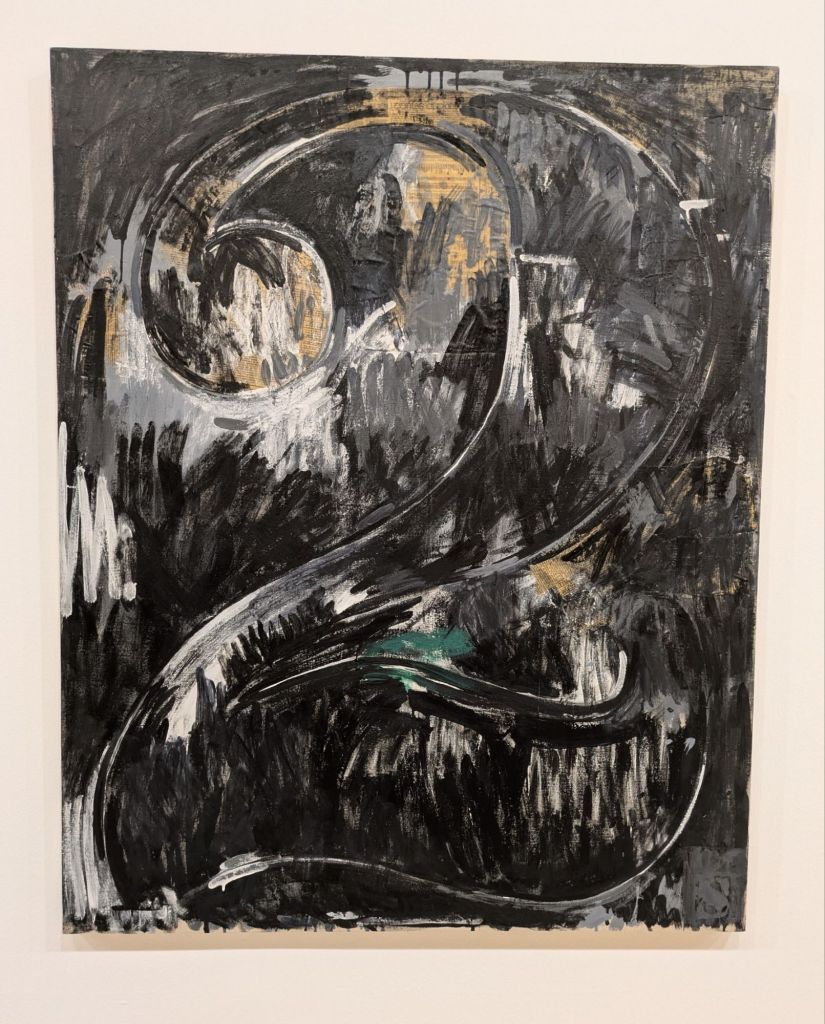

Of course this is conceptual but it is also made – the instruction is the existing work. There are Jasper Johns’ American Flags and numbers. The Figure 2 below is painted on newsprint and I can’t find one quite like it using Google.

Suze Kay discusses these works at length focusing on what sort of reproduction Sturtevant was making, pointing out that even though Sturtevant is using Warhol’s silkscreens, they are poorly made. Kay says “Especially in comparison to the original, but even alone, the unique nature of Warhol Marilyn is clear. The less-experienced Sturtevant produced a hazy image with poorly matched color fields. The boundary between the image’s cheek and hairline fuzzes into a dark smudge. Thin commas of turquoise sit haphazardly above the Warhol Marilyn’s eyes, just barely mimicking eyeshadow. The image’s surface is further flattened by the angry, sloppy smudge of red that slashes across its lips.”

Kay had earlier described an encounter with one of Sturtevant’s Frank Stella’s saying “Ingrid Langston … tells an amusing anecdote about a pair of viewers looking at one of her Stella repetitions. “Somebody walked in and said: That’s the worst Stella I’ve ever seen. And then somebody replied, Yeah, but the best Sturtevant.”

Sturtevant was subject to much hostility and largely ignored in the US. Kay describes her works as ‘cruel’ in what they do to the works of the male artists she is repeating.

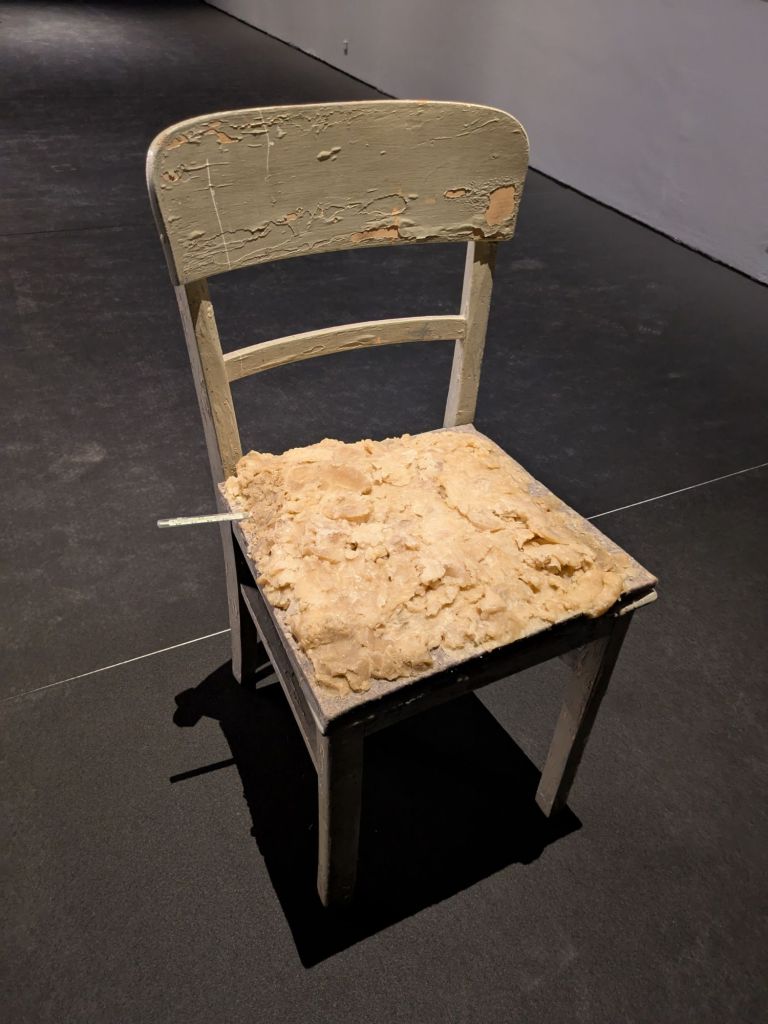

There is a room with two chairs and a set of windows – the windows are entitled Fresh Widow, a work made by Duchamp in 1920. There are 6 here and another in the Duchamp room. The chairs are attributed to Joseph Beuys.

One is entitled Beuys Fettstuhl and is, apart from not being ina climate controlled vitrine, very close to the one in the Tate, including the thermometer sticking out the side.

The other is entitled Beuys Vor Dem Pultstuhl and I’m not sure it is a copy though it uses wax and lead and brick and a leaf, all very evocative…

On one of the corridor walls we find a wanted poster (coincidentally with a dragonfly).

And in a room at the end of the exhibition a video entitled Sturtevant Re-Run.

The Sturtevant Estate is according to the captions represented by Galerie Thaddeus Ropac. They also represent Robert Longo and in an exhibition of his works where he was redrawing other artists’ works they quoted on the wall part of an essay by Dominique Font-Réaulx

“Longo’s ambition was to translate these paintings into his own language, to free the language imprisoned in a work by recreating it in his own style, to grasp, through a process of remaking and reinvention, the artist’s thought, which is discernible through intention and in gesture.”

Sturtevant isn’t translating into her own language (even when she is inventing new examples). Rather it seems to me she is questioning whether an artist’s language should be understood as singular, that the is any claim to uniqueness. She is certainly playing with Walter Benjamin’s argument about the aura of work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction – she is showing that the aura is a fiction. I might not be able to find the Jasper Johns’ Figure 2 (though I haven’t looked in a catalogue raisonne) but even if I did I would still be faced with a dilemma – can the copy also have aura?

We might need to turn to another Marxist critic Frederick Jameson and his argument that we have seen a shift in Capitalism from production to reproduction, “…how late capitalism transitions from an economy of production, where one makes objects, artworks, and commodities, where the output is a product, to an economy of reproduction, where signs, images, and ideas are the ever-circulating outputs.” as it is put in Ruby Thelot’s essay ‘Art Making Machines’. It’s interesting to consider Sturtevant in this light because there is specifically production here – it is the production of male artists’ works with in some cases a ‘disturbing degree of accuracy’ that opens up the questions about authenticity and power. Kay provides a valuable gloss on this point, “Sturtevant saw a piece of art as consisting of three main parts: the object, the process, and the concept. In an original work, the artist is responsible for the creation of all three parts. For example, when Johns made his original Flag (1954, figure 3), these parts were inseparable. But for Sturtevant, only concept mattered. “Although the object is crucial, it is not important,” she once said, a statement followed by “Process is crucial but not important.” Sturtevant, by mimicking the original artist’s process and pulling directly from their imagery, found herself responsible only for the content of an image. This unique approach of repetition allowed her work to directly challenge the artist’s original message, or as Langston says, is how she “called out other artists on their own claims.”.

Sturtevant isn’t the only artist who has resisted being associated with a specific movement, in this case feminist art, but for me she contributes a very important dimension – recent arguments made for the centrality of feminist approaches e.g. Heartney et al 2024 would be complemented by Sturtevant’s project. And the creation of a body of work that so effectively, even “brutally” in Sturtevant’s own terms, takes on the dominant male artists of the time and draws out the understructure the work is resting on must surely be understood as a project with a gender and political core?

What art have I seen? A Hundred Years of Biomorphism – Art and Nature

There are times you see something that could have been made yesterday but is in fact nearly 100 years old.

Exhibition from Pompidou collection including surrealism, land art, design, roughly grouped into 4 themes: Metamorphosis, Mimicry, Creation and Threat.

Besides the Len Lye work above it was interesting to see László Moholy-Nagy’s documentary film on lobsters. Also interesting to see Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty film and be reminded that he comments on the pink water resulting from the algae. (A year later in Survival Piece #2 the Harrisons use this characteristic of salt water algae to create a colour field/ shrimp farm/ salt works outside the LA County Museum.)

There is a good description of the exhibition here

What art have I seen? Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (CAAC)

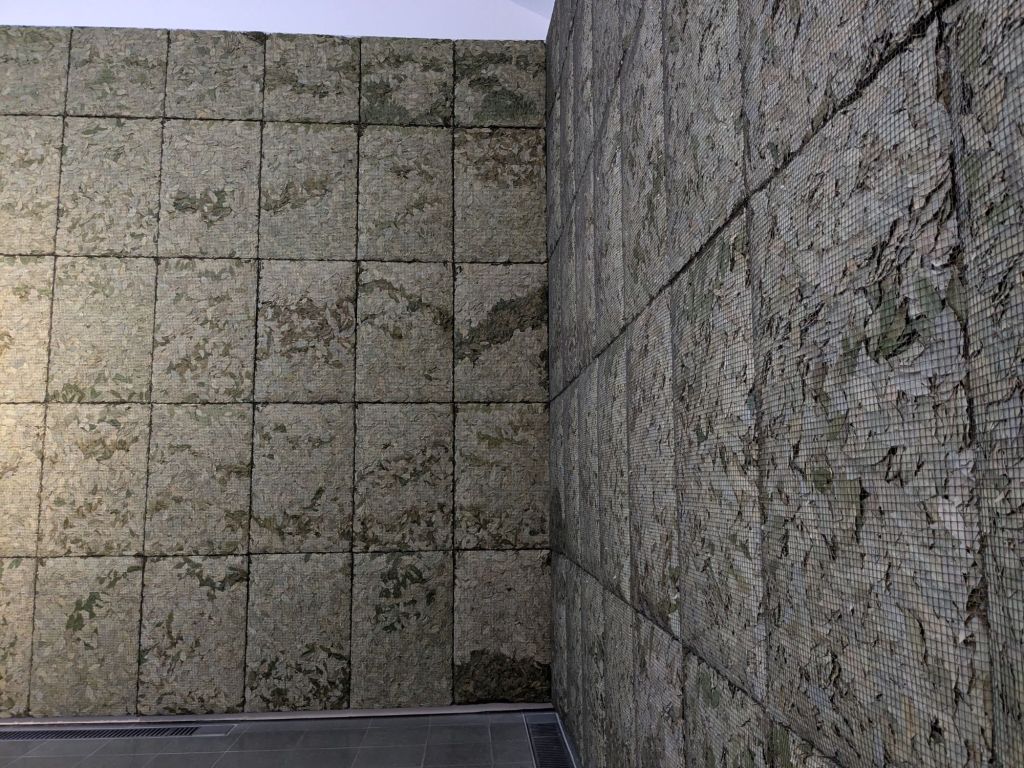

Multiple installations across former religious and ceramic production spaces.

Amie Siegal film work Asterisms exploring UAE culture in particular horses, more here

Louise Bourgeois installation

Kader Attia – Algerian French artist with works ranging from the beautiful and ironic through the deeply affecting to the angry and including some classic collages.

More in Attia here

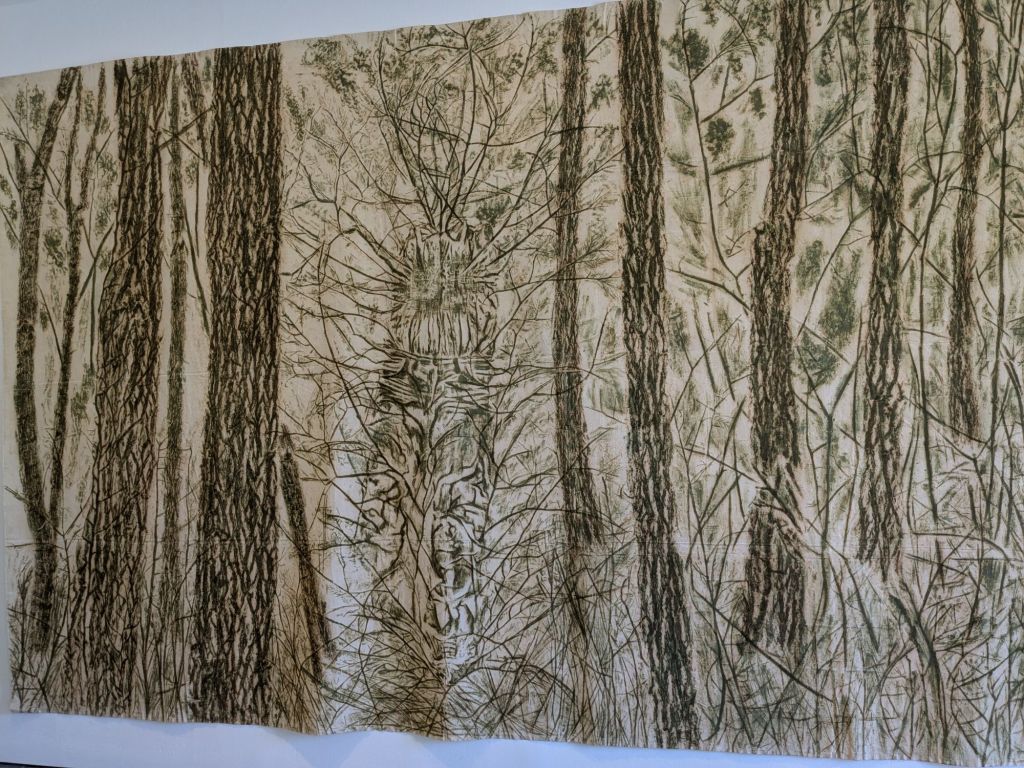

Regina de Miguel – Spanish artist – striking film on Rio Tinto and the origins of the Anglo/global mining business in extracting copper resulting in pollution and oppression. Interestingly it appears the Romans were here doing the same things. If you look at Rio Tinto on Google maps it’s about 40km from Seville and a destination sold on landscape remediation.

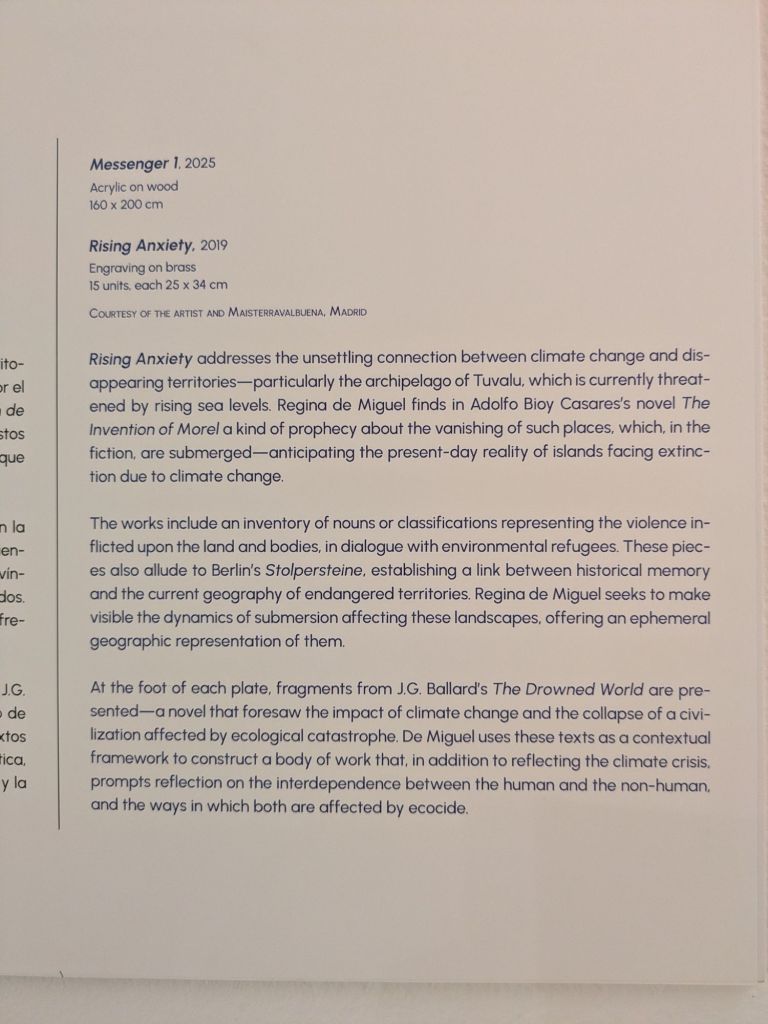

de Miguel’s work Rising Anxiety composes with maps, keywords, place-names, and quotes from JG Ballard’s novel

More on de Miguel here

What art have I seen? Knowing by Ear

Cristina Mejías, Knowing by Ear. Silent Singers; Wandering Apprentices. https://www.c3a.es/exposiciones-actuales/detalle/-/asset_publisher/pQ0PxnELFHyj/content/saber-de-oido-cantantes-silenciosas-aprendices-errantes-cristina-meji-1

Amazing new building – definitely architects let loose. Various other installations.

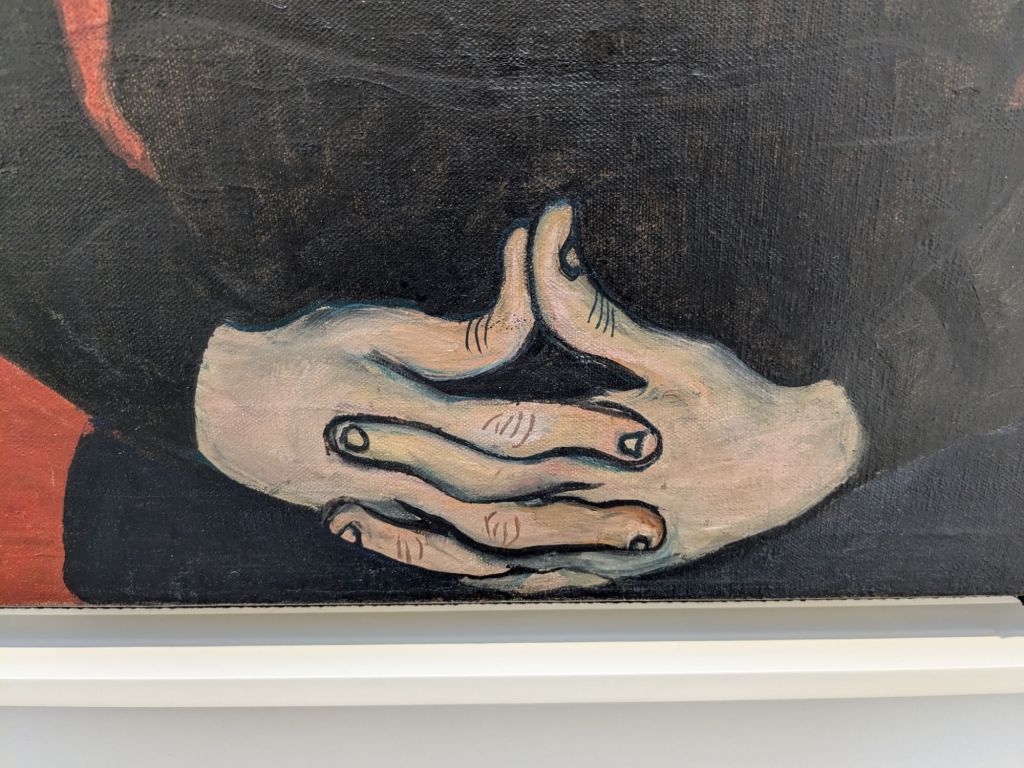

What art have I seen? Picasso Museum Malaga

More interesting than the one in Paris because it’s better curated, less about quantity.

Interesting attempt to break up the idea of ‘primitivism’ – would have liked that to be more developed: what aspects of which objects influenced Picasso in which ways?

Having seen ‘5 Friends: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Cy Tombly’ recently you can see why if Picasso so dominated the landscape you turn away from his approach to the rejection of constraint on thought or action… find other means.

What art have I seen? Museums in Munich

‘5 Friends: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Tombly’ at Brandhorst. Exploring various ideas that run through the different artists’ works – silence and nothingness – Rauschenberg ‘a White paintings, Johns’ White Numbers, Tombly’s, Cage’s 4’33”. Cage and Twombly’s Mushrooms. Duchamp an obvious presence.

Brilliant to see Cage’s collection of stones.

Pinakotek der Moderne had two really interesting exhibitions:

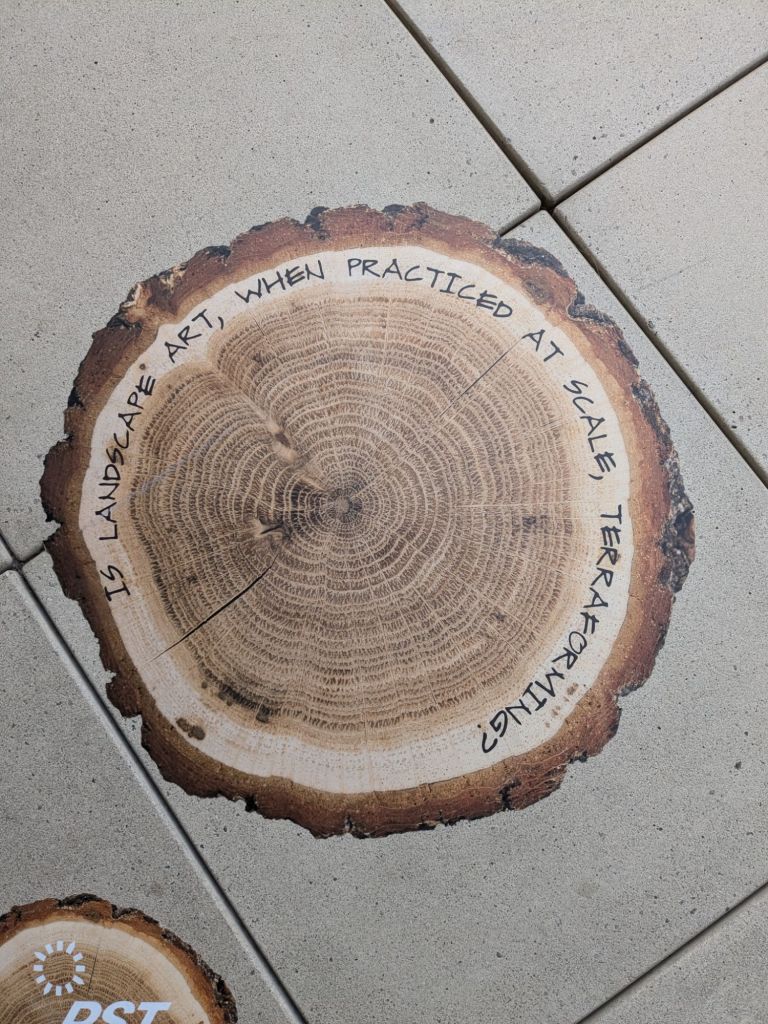

Trees, Time, Architecture: Design in Constant Transformation which explored experimental uses of trees in architecture and urban spaces. Really useful juxtaposition with all the artists’ projects. https://www.pinakothek-der-moderne.de/en/exhibitions/trees-time-architecture/

Yoshihiro Sunday: Garden Eden – beautiful selection from the collection juxtaposed with hand made weeds. https://www.pinakothek-der-moderne.de/en/exhibitions/garten-eden-naturutopien-japans/

What art have I seen? Electric Dreams

Art and technology before the internet at Tate Modern.

Good points: properly multi centred – yes US and UK but other European centres including in Europe – Italy, Germany, Zagreb, and then also Japan, Brazil and South America, etc.

What I’d like to have seen – the collection rooms (not the installation rooms) could have had non-art experiments to just make more visually viscerally clear how much this is a hybrid practice. A good example might be W Ross Ashby’s ‘box’ or homeostat.

The exhibition has a glossary room by room but there isn’t a timeline of the emergence of terms, and the history of the language of cybernetics is an important complement to the excellent diagram of the various artists and groups.

What art have I seen? Thoughts in the Roots

Giuseppe Penne at Serpentine Gallery. It looks so simple but every work is a labour and many are the result of decades of thinking and development.

What art have I seen? Fragile Correspondences

Scottish pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennial represented at the V&A in Dundee. Particularly appreciated the work on Ravenscraig by Amanda Thomson.

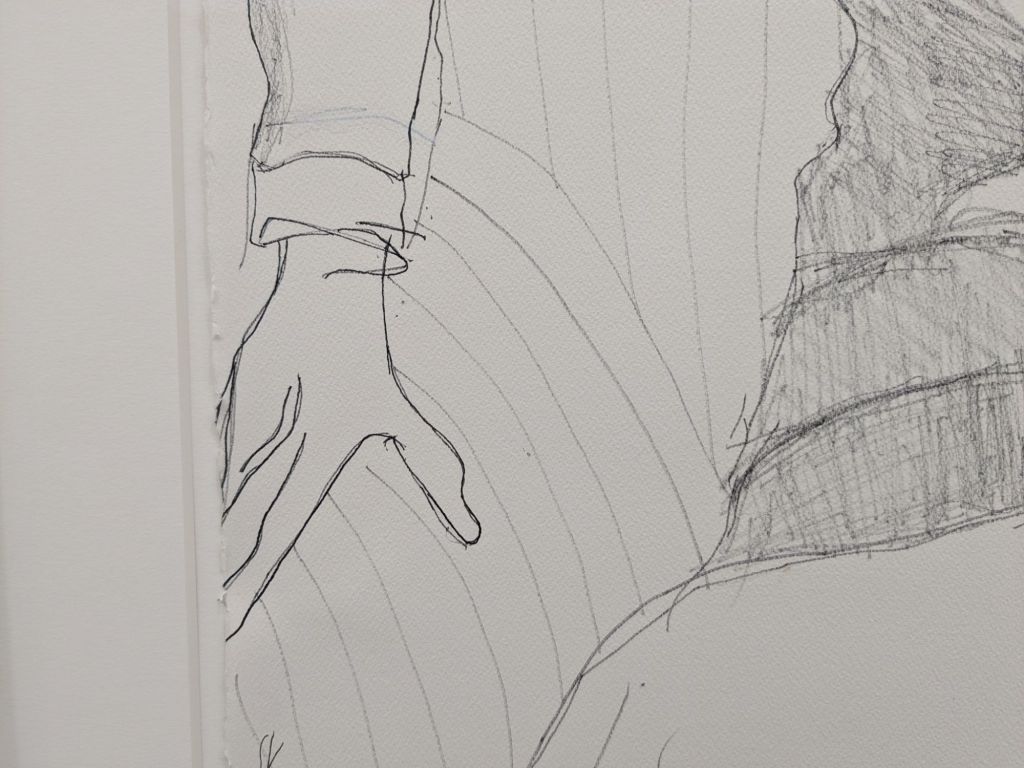

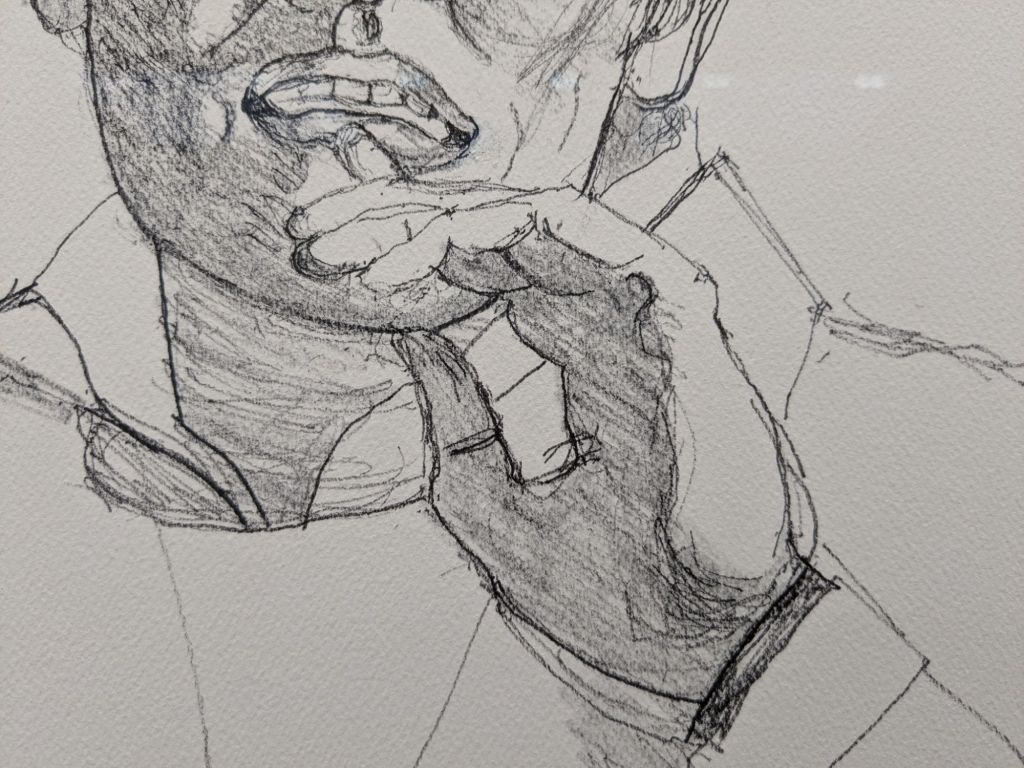

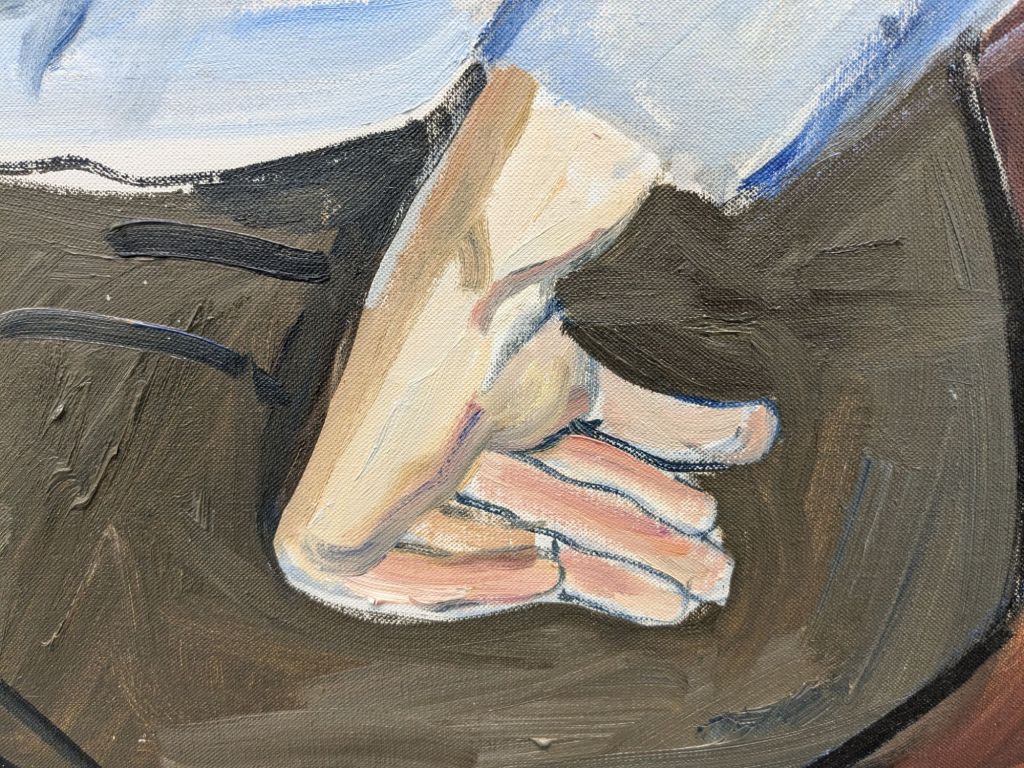

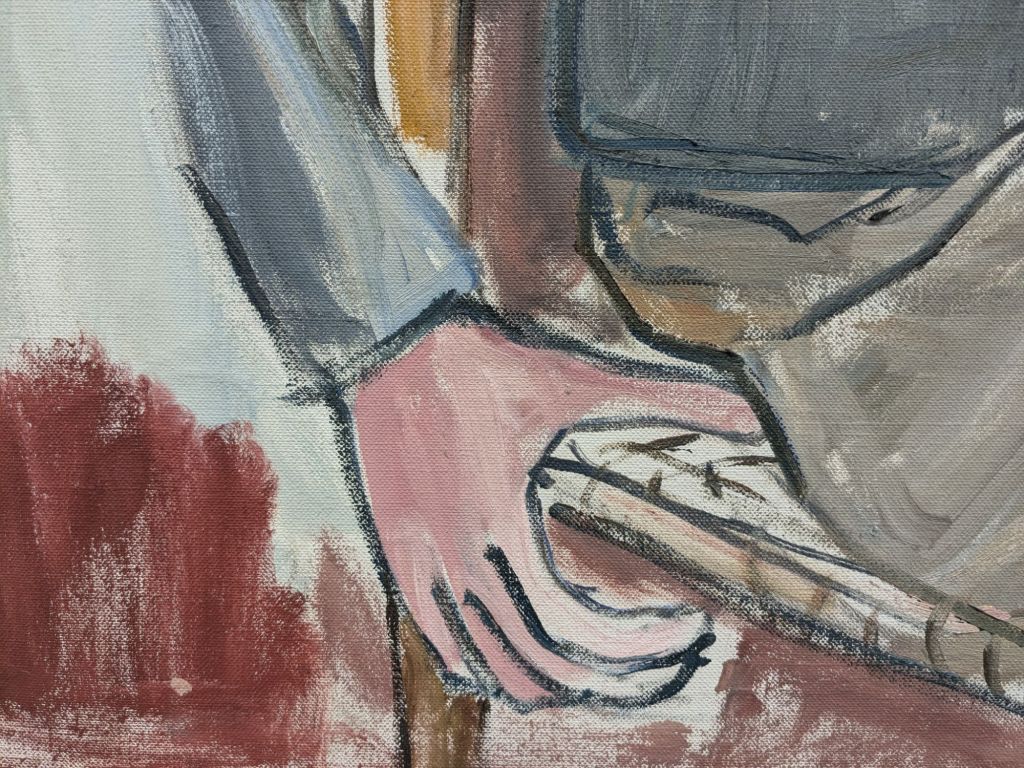

Christine Fremantle Portraits – do you know these people?

Christine Fremantle painted these portraits in London in 1992 and 1993.

If you know any of these people please contact me. Add a comment or email me – it’s first name @ surname.org

What art have I seen? Suzanne Lacy’s BETWEEN the door AND the street

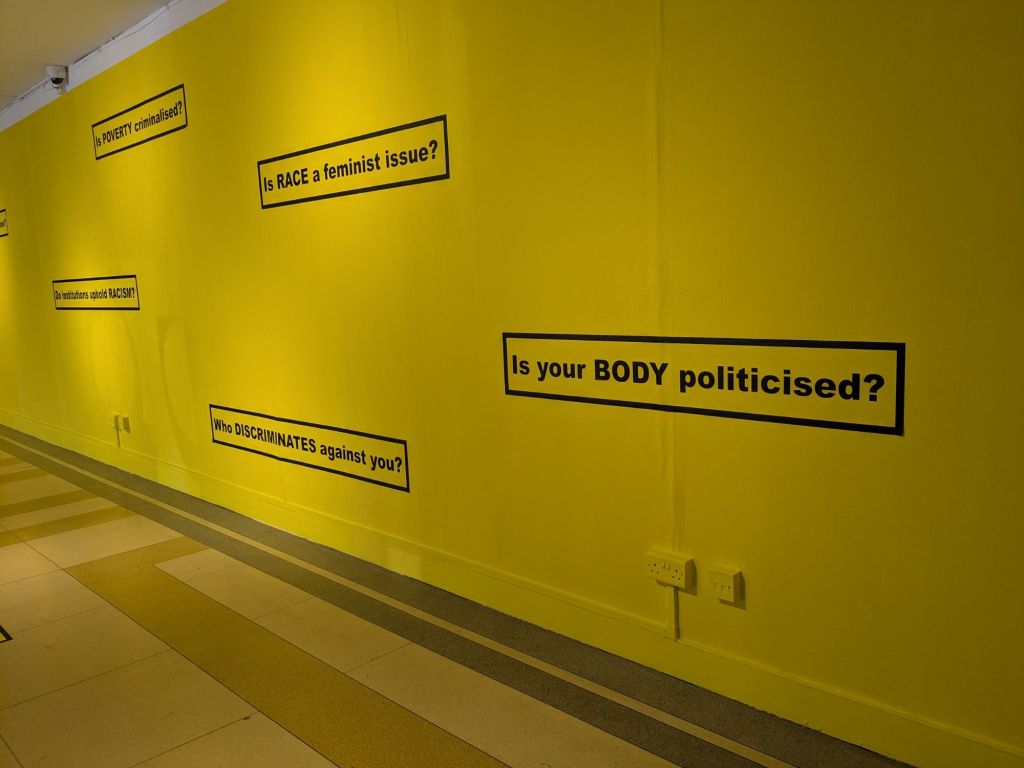

Really nice well conceived exhibition of a single work by Suzanne Lacy which opens up her practice. Currently listening to Suzanne Lacy in conversation with Cooper Gallery Director and Curator Sophia Yadong Hao. The importance of questions, emphasised by the entrance foyer space, the three channel video of the work, the study space…

Video below: Really useful and interesting conversation between Suzanne Lacy and Cooper Gallery Director and Curator Sophia Yadong Hao covering the image, audiences, safeguarding…

What art have I seen? Maud Sulter and Derek Jarman

‘Derek Jarman’s Modern Nature: Digging in another time’ at the Hunterian

‘Maud Sulter: You are my kindred spirit’ at Tramway

Pope.L on failure

“I’ve always been a little suspect of that term in the art world – well, because the people typically involved in the art world come from a culture that is not one of failure. And black people have seemed to be failing for many, many years. not of their own intention, obviously. I can get ignorance – you don’t know something, or you can’t know something. But failure? It was weird when I first started hearing this term thrown around. Why would anyone be interested in failure? But I realized some people are; they maybe think they are inoculated from failure. I guess I was intimidated by it. It’s something I have been avoiding all my life. Why would I want to deal with this shit? I mean, I’m already dealing with this shit. Why would I want to make it into an academic kind of thing? You know what I’m saying?” p9

A Field of Wheat: revisiting writing

I participated in artists Ruth Levene and Anne-Marie Culhane’s project created with farmer Peter Lundgren, and I wrote a piece for the project website – I was just reminded about it and thought it worth reposting. You can read it here and explore A Field of Wheat too.

Could an orchard installed in a gallery affect us (and the gallery)?

The strange orchard in a gallery invokes all the other orchards in the area, it invokes the employment, the harvest, the trucking, your parent working for one of the big juice businesses, the smell of the fruit in the warm evening air.

Just published on The Nature of Cities, an article on Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison’s ‘Portable Orchard’ https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2024/11/13/how-could-an-orchard-installed-in-a-gallery-affect-us-and-the-gallery/

What art have I seen? Embodied Pacific

More of the UCSD Visual Arts Dept collaboration with the Scripps Institute of Oceanography ‘Embodied Pacific‘ exhibition this time at the Birch Aquarium

What art have I seen? Embodied Pacific

Seaways at the Gallery in the Structural and Material Engineering Building.

Curious connections – Anson who featured in the Maritime Museum crops up again writing about how impressed he was with the boats built by Pacific Islanders…

The sail made of woven reeds was stunning.

What art have I seen? Transformative Currents: Art and Action in the Pacific Ocean

Oceanside Museum of Art – exhibition from around the Pacific rim. Stand out piece by Lutyens on the rigs off Santa Barbara.

What art have I seen? For Dear Life

Exhibition on Art, Medicine, and Disability at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego.

Really powerful exhibition starting with the Bufano dance piece, Act-UP, cancer-related, Nikki de Sant Phalle, so much interesting work.

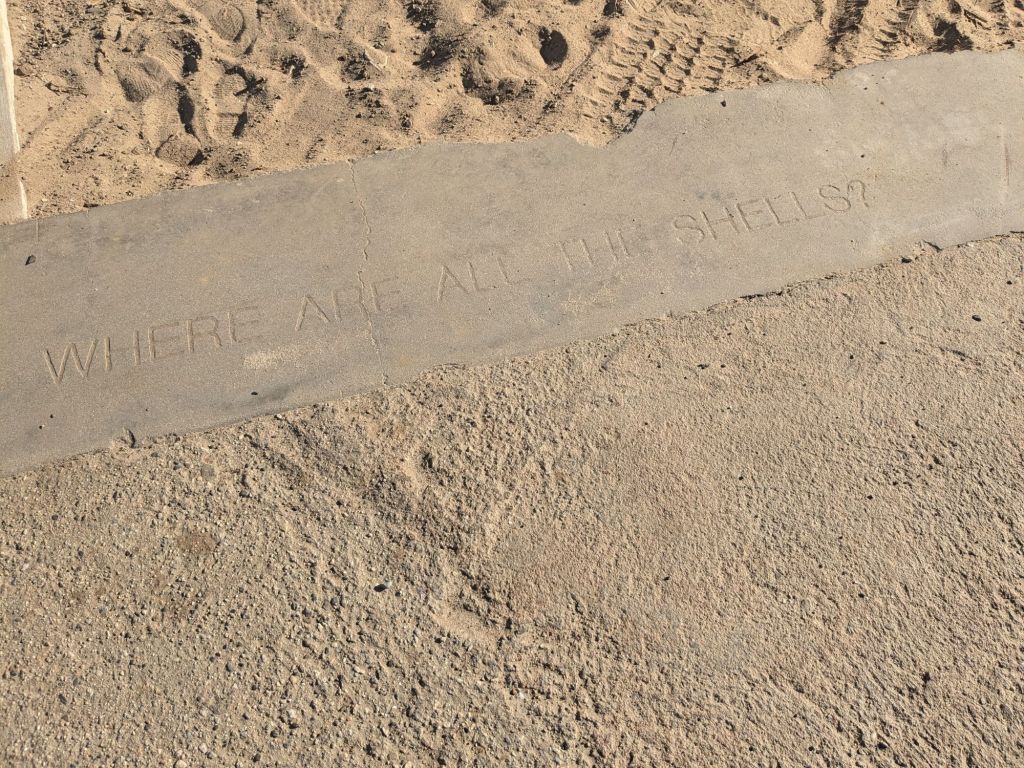

What art have I seen? Helen and Newton Harrison’s California Wash

California Wash is the only piece of ‘public art’ created by Helen and Newton Harrison (1989-1996) – they changed many landscapes but this is the only place you can see their concerns inscribed in a specific place – Bottom of Pico Boulevard in Santa Monica where it meets the sea. It doesn’t address the actual outfall, but it makes the place legible.

What art have I seen? Trees, Time, and Technology

‘Ancient Wisdom for a Future Ecology: Trees, Time, and Technology’ Exhibition at Skirball Cultural Center

What art have I seen? Breath(e):Towards Climate and Social Justice

Exhibition at the Hammer UCLA focused by the triple events #BlackLivesMatter, COVID Pandemic, and the Climate Crisis.

Featuring amongst other things a radical gardening project – and you can never have too many art and gardening projects! This one is led by Ron Finley, the gangsta gardener.

What art have I seen? Beatriz da Costa

A retrospective of da Costa’s brilliant projects including an ongoing re-performance of Pigeonblog. I wonder what re-performances of some of her other works would be like now? e.g. the RFID work with cockroaches?

What art have I seen? Life on Earth: Art and Ecofeminism

Margaret and Christine Wertheim are not wrong that Ecofeminism is underrepresented in PST. The new book Eleanor Heartney co-authored, Mothers of Invention makes the argument for the centrality of ecofeminism from the perspective of concerns in the arts – abstraction, craft, performance and ecology.

This is the exhibition that has Ecofeminism as it’s explicit focus. It is very much a sketch. It claims that Ecofeminism is an American idea. I wonder if the curators were aware of the much more substantial exhibition Re/Sisters: A Lens on Gender and Ecology which explicitly drew together a much wider narrative of the emergence and development which has a strong US representation but balances that with contributions from many other cultures.

Great to see Aviva Rahmani’s early performance work along with documentation of her durational restoration project Ghost Nets. The LA Times usefully focused on this in its review reviewhttps://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2024-10-15/pst-art-life-on-earth-ecofeminism-brick.

There is a good overview on ARTnews https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/life-on-earth-art-and-ecofeminism-exhibition-the-brick-los-angeles-1234722562/

What art have I seen? Future Tense

At the Bell Center for Art +Technology, UC Irvine

Future Tense: Art, Complexity & Uncertainty website

Claire L. Evans parses interdisciplinary experimentation at the Beall Center for Art + Technology

The exhibition is curated by David Familian who participated in the Listening to the Web of Life workshop – their paper here.

Cesar & Lois’ work Being hyphaenated (Ser hifanizado) is in the exhibition and they also participated in the workshop – their paper here.

Below is Fernando Palma Rodriguez’s Huitzlampa (2023)

“Huitztlampa, a mechatronic installation of everyday objects, is computer programmed to move in response to live weather signals from Los Angeles. Palma Rodríguez lives in a Nahua agricultural region outside Mexico City and wants his work to provide a heightened sense of urgency about both climate change and labor issues. In the pre-Hispanic Nahuatl creation story, four cardinal points are each associated with a deity: Huitztlampa, the south, is embodied by a hummingbird and the sun in the blue winter sky. This title and the objects (ladder, boots) also reference migrant workers, who must float like hummingbirds and move with the sun.”

Full descriptions of works here

and images here

What art have I seen? 500 Capp Street – David Ireland’s House

Photographs of the house and of installations by artists: Mildred Howard’s installation Collaborating with the Muses Part One (the large scale funnel installation in the back parlor, and the bird flying over the oyster shells), and Anne Albagli’s Milk Teeth (the carved limestone table in the dining room). There are no labels and the installed work sits in amongst Ireland’s interventions.

What art have I seen? Survival Piece #1: Air, Earth, Water, Interface: Annual Hog Pasture Mix

The first of the the Harrisons’ Survival Pieces re-performed* at Various Small Fires LA.

Having been invited to be part of ‘Earth, Air, Fire, and Water: Elements of Art’ exhibition at Boston Museum of Fine Art in 1971, they relate that Newton asked an assistant to find the most unusually named seed mix. They found ‘R.H. Shumway Seedsman’s Annual Hog Pasture Mix’. The Boston MFA wouldn’t let them have a pig on the pasture. In 2015 the LA Museum of Contemporary Art in LA allowed Wilma the Pig to participate. Today another pig participated.

* Tatiana Sizonenko, curator of ‘Helen and Newton Harrison: California Work’, currently on in San Diego as part of the Getty’s PST, frames these as performances rather than installations – processes rather than objects.

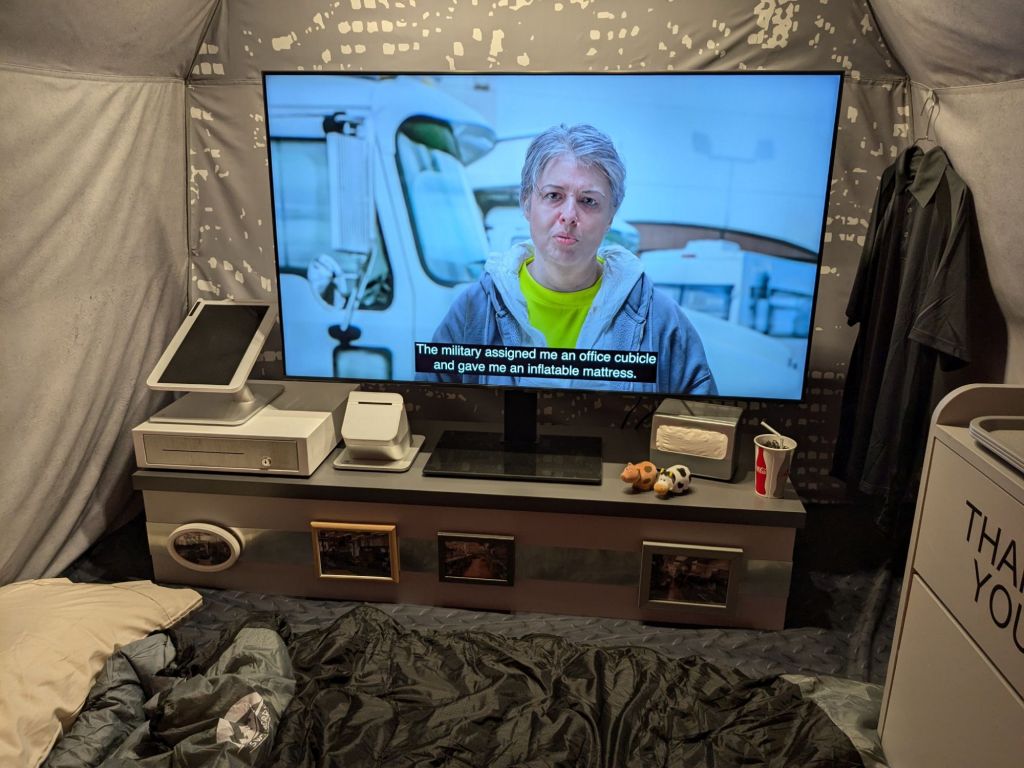

What art have I seen? Josh Kline’s ‘Climate Change’

The three chapters of Kline’s long term project are a stunning exploration of where we are, probably the most compelling evocation of business as usual. The first room has three places, cities, where melting ice blocks in the shapes of things like cars and polar bears raise the water level in the places.

The second room has three different buildings (a home, a mall, and a place of worship) all melting.

Then you enter a room with a bunch of tents, each one containing a video interview with a climate refugee – the water has risen and their everyday lives have melted away.

The tents have text on them

I pledge allegiance to my stuff…

The final rooms include hanging oil drums and then a video of some workers looking out over a drowned city, taking a break from the process of cleaning up or shoring up…

What art have I seen? Broad Museum

Everything in here is also in one of the top 8 commercial galleries –

- Artschwager Gagosian or Sprueth Magers

- Baldessari Sprueth Magers

- Beuys Thaddeus Ropac

- Bradford Hauser and Wirth

- Calder Pace

- Burden Gagosian

- Gursky White Cube or Sprueth Magers

- Koons Pace

- Sherald Hauser and Wirth

The relationship positively vibrates with the co-creation of value… This is the art world… The world of property development… Scarcity equals value…

The timeline is all about the quantities of works…

From a Broad Foundation press release:

Five Sherman works, currently on view through Oct. 2 in the museum’s first special exhibition, Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life, have been added to the collection, bringing the Broad collection’s holdings of the artist’s works to 129—the largest collection of Sherman’s work in the world. Four of the acquisitions are from Sherman’s most recent body of work, completed earlier this year and featuring the artist as aging film personas. The museum also acquired an important 1980 work, Untitled #71, from Sherman’s rear-screen projection series.

The Broad collection now has 11 works by Sherrie Levine, with the addition of her cast bronze Beach Ball after Lichtenstein, 2015, which questions ideas of originality and how value is accrued.

Media artist Ericka Beckman enters the collection with You The Better, a 16- millimeter film created in 1983. The 32-minute film explores games of chance and the powerlessness of players—and the viewer, drawn into the action—to affect the outcome. The acquisition also includes set pieces, shown with synchronized lighting, that together with the film comprise the installation.

The Broad also continues to build its collection of Los Angeles artist John Baldessari with a recent work, That’s Not Bad…, 2015, which brings the number of Baldessari works in the collection to 41.

Is this an art museum or a sports team? “Baldessari, a consistent scorer, is a favourite with the fans…”

What art have I seen? Eliasson and Dion

Olafur Eliasson at Geffen MOCA – lots of playing with light and reflection.

Mark Dion at La Brea Tar Pits – imagining paleo archaeology of LA.

What art have I seen? Helen and Newton Harrison California Work – ‘Future Gardens’ at Mandeville Art Gallery

The original Future Gardens proposal along with sketches 1996

Documentation of Sagehen A Proving Ground 2011 and of the Future Garden for the California Coast at the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum 2016

Tibet is the High Ground 1993

What art have I seen?’Helen and Newton Harrison California Work – ‘Saving the West’ at San Diego Central Library

What art have I seen? ‘Portable Orchard’ and ‘Time Landscape’

Credited to Newton Harrison at the time, but the 1972 work of Helen and Newton Harrison Survival Piece #V: Portable Orchard is now part of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s collection and is being re-performed. Tatiana Sizonenko (curator of ‘Helen and Newton Harrison: California Work‘ as part of PST in San Diego) uses ‘re-performed rather than re-constructed.

Downtown in Greenwich Village there is Alan Sonfist’s Time Landscape, a monument to the erased pre-colonial ecosystem of the island of Mannahatta, conceived in 1965 and realised in 1978. Now adjacent is an area of city gardens (or allotments), and a very large Picasso.

1 comment